Introduction

Our online catalogue shows that we hold somewhere around 94,300 photographs – these vary from glass lantern slides to 35mm slides and photographic prints. Obviously, we can’t look at all of them, but this presentation will show an eclectic smorgasbord of images taken from our collections that will hopefully be ones that you will not have seen before – although we will be throwing in a few of our favourites because…well, why not!

Domesday Book - Cheltenham

Courtesy National Archives

No examination of a county’s agriculture should ignore the Domesday Book. This was William I’s great 1086 survey to find out who held what land, its value and what taxes had been paid to the Saxon kings. It recorded landholders, their tenants, the amount of land they owned, how many people occupied the land, their class, plus the amounts of woodland, meadowland, the number of animals and ploughs on the land. This is the entry for Cheltenham and when translated from the Latin it reads:

KING'S LAND.

Edward held Chinteneham. There were eight hides and a half. One hide and a half belongs to the church. Reinbald holds it. In the demesne there are three plough teams, and twenty villeins and ten bordars and seven servi, with eighteen plough teams. The priest has two plough teams. There are two mills of eleven shillings and eight pence. To this Manor the King's steward added two bordars and lout villeins and three mills. Of these three mills two are the King's, the third is the stewards, and there is one plough team more. In the time of King Edward it (the Manor) paid £9 5s. and three thousand loaves for the dogs. Now it pays £20, and twenty cows and twenty hogs, and 16/- instead of the loaves.

First named farm, 1552

D674b/T18

The first named farm in the documents at Gloucestershire does not appear until the mid-1500s. It is named as ‘Bridgesburye farm’ (just left of centre on line nine) in this document which is a letters patent of Edward VI to Sir Anthony Kyngston, Provost Marshal and High sheriff of Gloucestershire, in September 1552. The farm was originally a possession of Cirencester Abbey and had passed into the Crown’s hands at the Dissolution, being granted to Kyngston later.

Manor of Kingsholm Court Leet, October 1791

D936/M11

The Manor was a method of land ownership (or tenure) during the Middle Ages and later. The size of a manor varied but it typically included a manor house (home of the lord and his dependants), a rural estate and a population of labourers or serfs who worked the land to support the lord for which they received certain rights and privileges. Manors maintained written records that included court rolls and surveys, maps, terriers, documents relating to the boundaries, wastes, customs or courts of a manor. The two courts were the Court Baron – which dealt with customs of the manor and offences against it, and the Court Leet – which dealt with enforcement of law and order within the manor. This page shows the part of the Manor of Kingsholm’s Court Leet for October 1791, appointing the jury and starting the presentments to the court.

Manor of the borough of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1719

D1395/II/2/M1

This page from the court leet of the manor of the borough of Stow-on-the-Wold for 1719, shows one of the issues if you want to research manorial documents. Until 1733, manorial records are likely to be in Latin and, both before and after that date, in handwriting that can be difficult to read.

Post-enclosure map of Homestallend, Todenham, 1593

D1099/P1

Small enclosure had been ongoing since the medieval period - to create warrens and deer parks. This map is a post-enclosure map of Homestallend at Toddenham, which was enclosed in 1593. The legend at the top-left of the map records that the land “which laye dispersed by ridges amongst the tenauntes and nowe by consente every mans portion layed togethers.” The ‘Enclosure Movement’ however was on a national scale and was instigated by upper class landowners. Initially enclosures were all undertaken by private Act of Parliament, but such was the momentum of the upper classes, in 1773 an Act of Parliament was passed to legalise enclosure – provided a systematic process and certain conditions were observed. Part of this was that impartial commissioners were to be appointed to oversee the process in a fair and just way, although this was rarely the case. The argument of those behind the enclosure movement was that by enclosing open fields, merging and re-distributing land, it would reduce waste, improve efficiency and bring new investment and agricultural advances that could increase food production (…and profits for landowners).

A survey of Aston Blank, alias Cold Aston, in Gloucestershire the Estate of Sir Thomas Doyly, Bart., 1752

D2231

This amazingly detailed and very large estate map shows the nucleated village of Cold Aston (aka Aston Blank) surrounded by four extensive open fields showing the long narrow (mostly ¼-acre) strips of land held by tenants and freeholders for cultivation. While the boundaries of the open fields are marked in bold red lines, the emerald lines are probably hedges delineating fields for grazing animals. The map gives a good sense of the open-field system which was in use prior to the enclosure acts. In this system, all arable land was divided into many long narrow strips for cultivation. An individual tenant’s or freeholder’s holding, consisted of about 20 acres of land lying in 70 or so strips, scattered all over a manor with no two strips lying together. This reinforced the need for co-operative farming as the strips were unfenced and the same crops were grown. This type of cultivated landscape came to be known as ‘ridge & furrow’. Technically every parish that was enclosed was supposed to have a pre-enclosure map as part of the enclosure process – but few survive.

A Map Plan and Admeasurement of the Parish of Cold Aston, 1795

D75/P1

Cold Aston was enclosed in 1796 but today only the Award survives. However this map is an unofficial post-enclosure map of Cold Aston or to give it its full title – ‘A Map Plan and Admeasurement of the Parish of Cold Aston, otherwise Aston Blank, in the County of Gloucester made for the purpose of being annexed to that part of the Award which is directed by Act of Parliament to be deposited in the Parish Chest of the Church’. It is orientated to match the orientation of the previous map. Where the earlier map shows hundreds of individual strips spread across the four open fields, this map shows the parish lands divided amongst the main freeholders and some of the tenants. In the pre-enclosure map, the parish poor had numerous strips of land across the parish – in the post-enclosure map, this is greatly reduced to just one field.

Dowdeswell tithe map and apportionment, 1838

GDR/T1/69

This is part of the 1838 tithe map of the parish of Dowdeswell. Tithes were a 1/10th in kind contribution of produce given to the church from 855 onwards. They were divided into two forms; Great Tithes (the products of crop husbandry, i.e. things that grew every year from the ground such as corn and hay) and Small Tithes (the product of animal husbandry such as milk, meat, egg, etc and the work of men). As an ‘in-kind’ payment, churches had to build places to store it, typified by tithe barns. However by the late 1700s, tithes were seen as a major obstacle to agricultural improvement, and they provoked anger and bitterness towards the Anglican church. In 1836, in-kind tithes were abolished and replaced with money by the Tithe Commutation Act. The Act required the drawing of an accurate map showing all the land in the parish and the creation of a schedule or apportionment which listed the owners, occupiers and a description of the land in the parish including individual fields. The process was certified by commissioners although it was the landowners not the church who had to pay for the process! The series of maps resulting from this legislation provide unprecedented coverage, detail and accuracy (many included field names) creating a wonderful snapshot of agriculture in the mid-1800s. Tithes were finally abolished in 1936 – mostly due to pressure from non-conformist religions who argued that it was unfair that the Anglican church received tithes while other religious organisations didn’t. – and a complex system of payments were created with the final amounts not being made until 1977.

Little Barrington Churchwardens Accounts, 1771

P37/CW/2/1

By the 1500s, the population of Britain was finally recovering from the Black Death, but agriculture hadn’t greatly changed and the mix of a growing population but low crop yields, meant food was scarce. To try and increase farm yields and fend off food shortages, the Tudor monarchs introduced a series of acts to try to control pests and ‘vermin’ that were thought to destroy and consume crops. The most complete act was Elizabeth’s 1566 ‘An Acte for the preservation of Grayne’ which included a list of the species that were classed as vermin and the bounty (amount of money) people received for killing them. This entry in Little Barrington’s churchwarden’s accounts for 1771 and shows money paid for ‘urchins’ (hedgehogs), sparrows and sparrows’ eggs. Hedgehogs were hated as it was thought – wrongly – that they drank milk from cows when the latter were lying in fields at night. And also stole eggs. In the book ‘Silent Fields’ (Lovegrove, R., 2007, Silent Fields, Oxford University Press) it is estimated that in the years when the Vermin Acts were being enforced (1660 to 1800) well over half a million hedgehogs were killed. In the parish records of Painswick and Great Badminton, the churchwardens accounts 2,557 and 2,696 hedgehogs killed respectively. A hedgehog was worth 8d….about £2.91 today. Sparrows were also heavily targeted – primarily because it was thought they damaged crops and (thatched) buildings – and as well as being shot, they were caught in clap-nets and sparrow pots. Between 1700 and 1930 it is estimated that 100 million sparrows were killed and it was still legal to catch and kill sparrows up to 2005. Th Great Barrington accounts here show that 3½ dozen sparrows – 42 birds – were worth 7d …. about £2.50. It cost more to wash the surplices…..

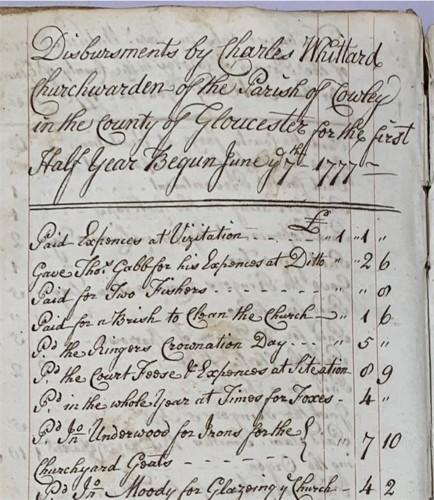

Cowley Churchwardens' annual accounts, 1777

P102/CW/2/1

This extract from a page of the Cowley churchwardens accounts for part of the year 1777 lists monies for ‘fishers’ (Kingfishers) and Foxes. The Kingfisher may seem to be an odd inclusion for an ‘An Acte for the preservation of Grayne’ but the bounty had been in force since medieval times because it was deemed that Kingfishers were competitors with man for fish, even though they only took small fish such as sticklebacks and fish fry. This can be laid at the door of the Roman-Catholic faith because as Catholics were required to abstain from meat on Fridays (in remembrance of the Lord's passion, and as an act of communal penance) they ate fish and saw Kingfishers as a threat to fish stocks. The presence of Foxes in this list (‘Pd. In the whole year at times for Foxes’) is interesting for although Foxes were widely despised for their constant depredations on poultry, lambing flocks and piglets, they were also considered a valid ‘beast of the chase, so their presence was encouraged. The English chronicler Holinshead wrote that ‘if foxes were not preserved for the pleasure of gentlemen they would be utterly destroyed manie years agone.’ Foxes that appear in the parish accounts however were not killed for sport but because of the predatory nature. What is certain however is that fox populations in the past – despite their persecution – were lower than in modern times. As the bounty on a Fox’s head was 1s, in 1777 at Cowley 4s was paid out so four Fozes must have been killed. This is possibly and average figure for the parishes in the county overall, although in 105 years of accounts from Newnham, in the Forest of Dean, 612 foxes were listed as being killed, an average of 5.8 a year.

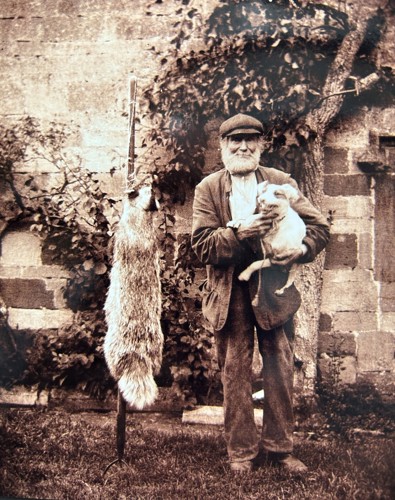

Dead badger and gamekeeper with dog, early 1900s.

D15345b/2

Taken from an album of photographs of Bishops Cleeve, Woodmancote and surrounding areas, this sad image was probably taken at Manor Farm, Alstone (between Teddington and Toddington) in the early 1900s. Badgers were hunted mercilessly, and it is amazing fact that the species survived at all and wasn’t hunted to extinction along with the other larger predators of the land. What saved them was that they tended to be nocturnal and so may have escaped attention being out of sight in the day. Badgers were hated as they were thought to steal chickens, kill young lambs and take eggs from birds’ nests and their setts could undermine the edges of fields and destroy land that could be used to grow crops. Consequently, a badger’s head was worth 1 shilling (£4 today). They were also considered beasts of the chase and even worse, were frequently dug out and taken alive to be used in badger baiting. Despite this practice having been banned 190 years ago in 1835, the fact that it still goes on today is sickening. Killing badgers was still legal in Britain until the introduction of the 1992 the Protection of Badgers Act and even today, badgers can be killed if they are suspected of passing on bovine TB.

Example Farm, Cromhall c1881

1881 1st Edition reproduced with the acknowledgement of the Ordnance Survey

Despite its social implications, enclosure did bring new investment and improvements into farming– and this gradually triggered or built into what is termed the ‘Agricultural Revolution’. Foremost among these changes were the Victorian ‘Model farms’ or ‘Example farms’ - this is Example Farm at Cromhall. The philosophy behind these new farms was that agriculturally knowledgeable landowners could show their less fortunate neighbours and their tenants the way to increase their income and crop yields through new farm buildings, new technology and improved farming methods. Although many farms remained as mixed farms, some began to specialise in either livestock or arable farming – heralding the modern farm of today.

Scything hay at Bisley, c1900

D9746/1/9/367

After enclosure and model farms, mechanisation became the third critical improvement to improving the nation’s agriculture. Hay was the primary fodder for livestock during the harsh winter months when fresh grass was scarce. This hay was made from grass, cut and dried in the sun to preserve it. The first stage of the hay harvest is the cutting of the grass and prior to the mid-1700s cutting grass relied upon men using scythes, as seen here in the wonderful photograph taken around Bisley in the early 1900s. Scything was not arduous work but was labour intensive and took time, primarily because every now and then, the scytheman would have to take a break to sharpen the scythe’s blade, which was undertaken by using a gritstone. Occasionally, if the scythe blade hit a stone or a particularly tough stalk, the blade might have to be peened as well as resharpened. However as mechanisation dawned, horse-drawn mowers replaced scythemen, seed drills replaced broadcasting, and mechanical threshing machines made farms more efficient – all because they required fewer men so making farming more efficient. The two biggest, most-labour intensive and important times in the farming year – hay making and harvest time, were revolutionised by mechanisation.

Mowing hay at Copsegrove Farm, Bisley

D9746/1/9/369

This photograph shows haymaking at Copsegrove Farm, Bisley and features two horse-drawn mowing machines. The mower used a cutting bar with fixed sharp, triangular teeth and a reciprocating knife blade that was chain-driven and powered by the rotation of a driving wheel on the ground. As the horses walked, the driving wheel turned, driving the reciprocating blade which cut the grass as the machine moved forward. These machines are probably American makes (possibly Jones’ or McCormick models), which were popular in Britain at the beginning of the 1900s. The machine was operated by a farmer sat on the seat and the controls were a clutch, a lever to swing up the cutting bar away from any obstacles and another lever to regulate the cutting height by rotating the cutter bar. The cut grass was laid in swaths called windrows and the next step in hay making was to dry it. This was achieved by throwing and spreading the grass about. Known as tedding, the tools used were wooden rakes – one of which can be seen with the man on the right. The white bench-like object man with the man on the second right seems to be a portable stand upon which the mower’s cutter bar could be sharpened.

Hay-tedding machine with Percy Lacey, Cam, c1900.

GPS/69/26

Mechanisation also came to tedding hay. The first hay-tedding machine was designed by Robert Salmon of Woburn in the early 1800s, but it was not until the latter part of that century that the development and use of the hay-teddder became widespread. This photograph shows a horse-drawn tedder made by the Upthorpe Iron Works of Cam. The man is Percy Lacey, son of the owner of the ironworks, Felix. This tedder appears to throw the hay in the windrows upwards as the tines presumably rotate via a chain-drive from the wheels.

Hay baling at Bisley, 27 September 1917

D9746/1/9/372

This atmospheric picture is more complex than it looks. Once the hay had dried it was pitched onto a wagon and then taken to be either formed into a rick or in later times baled. The creation of hayricks was a laborious task, often involving the collective effort of the community, and their construction required skill that meant that the hay was stored in such a way that it would prevent spoilage and rot. The shape and size of hayricks could vary, but the aim was always to ensure that the hay remained dry and ventilated. This was important because damp hay could develop mould, making it unsuitable for livestock and potentially causing health problems for animal and man alike. The art of hayrick construction became a skill as prized as any other aspect of farming and the most skilled practitioners were often in demand during the haymaking season. The most important part was creating maximum protection from the elements and so the art of thatching hayricks was refined, with thatched roofs becoming more common as a means of shielding the hay from rain and moisture. During the 1800s, a significant development occurred with the invention of the hay press. This manually powered machine compressed hay into compact bales, which were easier to handle, transport, and store. The advent of baled hay led to a gradual decline in the traditional hayrick, particularly on larger, more mechanised farms. By the start of the 1900s, static mechanical hay balers powered by traction engines had been introduced which continued the speeding up of the haymaking process. This photograph shows a Ruston mechanical baler being driven by a traction engine at Rectory Farm, Bisley in 1917. Five of the nine men visible are soldiers – haymaking was vital to the war effort and so the War Office released soldiers to help.

Jellyman family haymaking at Brownshill, Stroud, early 20thcentury

D9746/1/6/4

Mechanisation continued apace and by the 1920s towed mechanical balers had been developed, as seen here in this photograph of the Jellyman family haymaking at Brownshill. These gathered dried hay from the windrows and compressed them into bales. A knotter device then used the ubiquitous ‘baler twine’ to bind the hay together into a bale. The bales were then dropped behind the baler and could be collected on a wagon and then taken to the farm for storage.

Mrs Watkins and daughter Emmie, harvesting, Forthampton, 1905,

GPS/146/50

After haymaking, harvest was the most important time of the year for farming and it was a real case of ‘All hands to the pumps’ – as late as the 1970s a farmer’s family & friends would often visit the farm at harvest to help. This atmospheric image shows Mrs Watkins and daughter Emmie collecting corn to make stooks.

W S Browning & Sons threshing machine

D9746/2/361/14

This is the threshing machine of W S Browning & Sons of Stonehouse in operation. Powered by steam, initially by portable engines and later – as seen here – by traction engines, threshing machines revolutionised the harvest. This threshing machine was made by Marshall & Son's of Gainsborough. Stooks of corn were fed into the thresher at the top, and inside, it separated the grain from the stalks and husks, letting the grain fall out to be bagged, while the straw was carried to the far end of the machine , where it could be collected and put into onto a rick or fed into a mechanical baler and baled. Threshing machines heralded the start of the agricultural contracting business as they were wheeled and could be towed from farm to farm by the traction engine. The widespread introduction of threshing machines were largely responsible for igniting the Swing Riots of 1830-31!

Combine harvester at work, c1960

D10638

By the late 1950s, modern farmers were harvesting using combine harvesters – essentially self-propelled threshing machines. Here, a tidy Massey Ferguson MF 400 combine is emptying grain onto a trailer – towed by a Massey-Ferguson 135 tractor (the latter thrived under the nickname of the ‘Red Giant’).

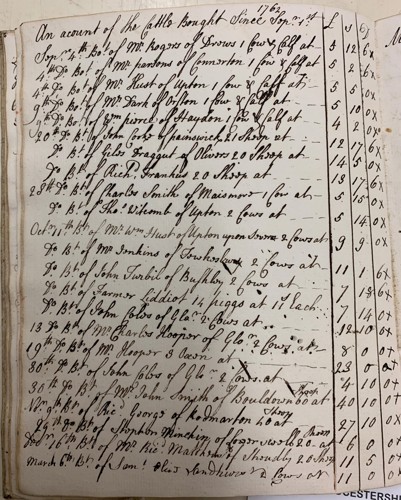

Farm memo book of Thomas Cother of Longford, 1762

D177/VII/3

This 1762 memo book of Thomas Cother of Longford, records payments for cattle (and other animals) bought from September 1762 to March 1763. It lists the sellers, the locations, the animals and the amounts. shows various animals, including 3 oxen for £23 (around £2,360 today), 14 Pigs at 11s each £7 14s (£789 today), 21 sheep for £12 17s 6d to 14 5s (£1,319 to £1,460). The price for a cow and calf ranges from £4 2s to £5 12s 6d (£420.10 to £576.35). Today an average price is very variable but depending on the markets is around £350 for a cow, £334 for an ox, £84 for a pig and £80 for a sheep.

Milkmaid & cow, Sydenham Farm, Moreton-in-the-Marsh

D9746/1/9/63

Cattle were popular in the Vale but later spread up into the Cotswolds. Most cattle were bred for milking – this is milking time at Sydenham Farm near Broadwell in the north of the county.

Gloucester cow

D10554

The Gloucester is one of the rarest native cattle breeds in the UK, originating in the Severn Vale sometime in the 13th century. They are strikingly beautiful with a black-brown body with black head and leg and a white stripe that runs down the back, over the tail and down over the udder to the belly. A true all-purpose breed they were valued for their milk (for Single and Double Gloucester cheese – which traditionally was only made with milk from the breed), their beef, and for providing strong draught oxen. And if that wasn’t enough, they saved the world from smallpox, for it was a Gloucester – called Blossom – that provided Edward Jenner with his first smallpox vaccine. Today they are classed as an endangered rare breed, but the Gloucester Cattle Society is doing excellent work to save them.

Herding pigs, Chipping Campden

GPS/81/190

This photograph shows a woman herding pigs in the High Street of Chipping Campden beside the ‘Live and Let Live Inn’. It is likely that the pigs were being taken to the market – but you wonder what chaos they caused on the way! Gloucestershire was home of course to the Gloucester Old Spot, which was nicknamed the ‘Orchard Pig’ or ‘Cottager's Pig’. It originated in the Vale of Gloucester in the 1300s and they are the oldest pedigree pig breed in the world. When the GOS Breed Society was formed in 1913, the breed was called 'Old' Spots because the pig had been around for as long as anyone could remember! Oddly, the first pedigree records of Old Spot pigs only start in 1885, far later than those of cattle, sheep and horses because as an animal, the pig was deemed a peasant's animal, a scavenger and was never highly regarded!

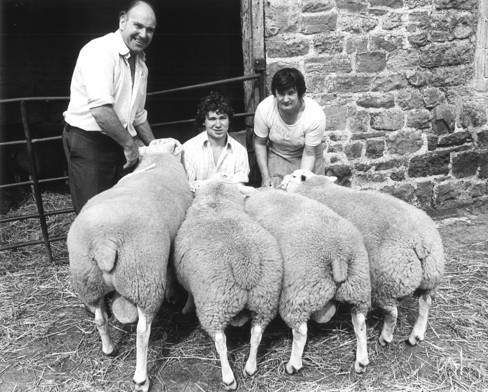

Prize rams

D10638/1/1984

Usually described – by sheep farmers – as ‘an animal looking for new ways to die’, sheep have been in Gloucestershire since the Iron Age and possibly before. Despite numbers falling from their medieval peak, there are still around 260,000 sheep in the county. Gloucestershire has two traditional breeds of sheep. The first are the Cotswold Sheep, which are probably a cross between an Iron Age breeds (i.e. Soay sheep) and a Roman long wool breed. Their wool was known as the 'Golden Fleece' owing to its rich lustre and was a big export in the Middle Ages. They played a key role in the development of many Cotswold towns and villages, but also in the finances of the nation - at one time flocks of 6,000 sheep were common but times have changed, and they are now classed as a rare breed. The other breed is the Ryeland Sheep, which are a white-faced, polled (no horns), small to medium, dual-purpose sheep, that are still popular today. They first appeared in the West Gloucestershire-Herefordshire area, with the monks of Leominster playing a leading role. They were named because they were commonly grazed on rye pastures.

Breaktime at haymaking, c1900

GPS/69/24

One of the best things about ‘draying’ bales at haymaking and at harvest time is crib time! Here a group relax with food and drinks – note the China cups, the wicker-covered bottle and the hay rake in the hedge. We will close this exhibition with a few lines from the famous Forest of Dean poet F. W. Harvey’s After Long Wandering.

I will go back to Gloucestershire,

To the spot where I was born,

To the talk at eve with men and women,

And song on the roads at morn.

And I’ll sing as I tramp by dusty hedges,

Or drink my ale in the shade,

How Gloucestershire is the finest home,

That the Lord God ever made.