Gloucestershire Mariners

Alexander Johns owned and managed Gloucester’s largest fleet. He was born in Liverpool and moved to Gloucester with his family. His father established a business in ship repair and Alexander worked with him. They repaired ships in the dry docks and had a tinsmith business in Llanthony Road. Alexander then went into narrowboat ownership and eventually bought seagoing vessels. Part of his work was buying wrecked or stranded craft and selling them on as barges or putting them back to sea. His house was in Southgate Street and his offices were in Commercial Road, now part of the Food Dock.

The list above dates from 1910 in Lloyd’s register, the first figure is the date the boat was built the second it’s registered tonnage.

The Nurse Family

The Nurse family interests eventually spread from Gloucester to Bridgwater in Somerset. Nautically they spread out from Epney and the family are linked to many others through marriage. John Nurse lived and worked with the Hillman Family.

Charles and Frank Nurse were brothers who lived round the corner from one another in Kingsholm. Their offices were in Commercial Road opposite Alexander Johns. They owned ships and managed them, sold chandlery and made sails. Frank Nurse remained a Master leaving Charles to run the business. Frank was lost with the Lucy Johns in December 1910 when she sank in a storm in the Irish Sea.

Kittel Pedersen

Kittel Pedersen was a shipwright and later boat owner and manager who moved to Gloucester in the 1890’s. As trade flourished there was an influx of workers from across Britain and Europe to work in the city. Kittel Pedersen worked with Alexander Johns and was managing the Lucy Johns when she was lost in 1910.

Kittel Pedersen was a shipwright and later boat owner and manager who moved to Gloucester in the 1890’s. As trade flourished there was an influx of workers from across Britain and Europe to work in the city. Kittel Pedersen worked with Alexander Johns and was managing the Lucy Johns when she was lost in 1910.

His newspaper obituary describes the vibrant maritime world of Commercial Road where everyone was involved in the sea trade, supplying ships with work, crews and the equipment for their working business.

Lucy Johns

The Lucy Johns was the pride of Gloucester’s sailing ships launched from Cocks Yard in Appledore, North Devon. She was registered in 1897 and named for Alexander Johns wife. Carrying around 250 tons she was schooner rigged. Frank Nurse became her skipper from the second voyage when her previous master, Mr Camm died in Antwerp.

The Lucy Johns was the pride of Gloucester’s sailing ships launched from Cocks Yard in Appledore, North Devon. She was registered in 1897 and named for Alexander Johns wife. Carrying around 250 tons she was schooner rigged. Frank Nurse became her skipper from the second voyage when her previous master, Mr Camm died in Antwerp.

The ship worked in the Home Trade but never traded to Gloucester. In December 1910, she loaded 180 tons of oats for Southampton in Ballinacurra near Cork. She sank on the night of the 16th December 1910, lost with all hands in the company of the Victoria and the Beatrice Hannah, both with masters from Gloucestershire.

Festus Agrippa Roberts

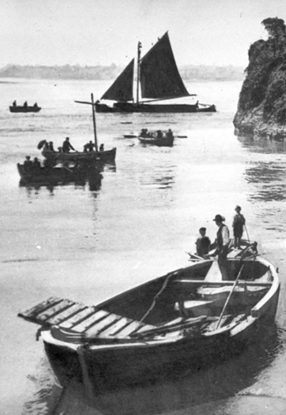

Captain Roberts on the right with his crew on the Hibernica which he owned.

Captain Roberts on the right with his crew on the Hibernica which he owned.

Festus Agrippa Roberts was born at the coal wharf on the Stroudwater Navigation at Eastington in 1870. When he was 14 he went to sea and served in several small sailing boats in the ‘home’ or coastal trade. At the age of 18 he studied for a navigation qualification and then took a job on a deep-sea ship from Sharpness. He sailed round the world twice. In 1904 he got married and settled back to a life in the home trade. He was related to the Nurse family and when John died in 1910 he was asked by Margaret Nurse, John’s widow and the new owner of the boat, to be master of the Beatice Hannah, a ketch. He was lost carrying a cargo of malt from Ballinacurra to Dublin in the same storm as sank the Lucy Johns.

The Stamps of Epney, a double tragedy.

Carrying around 140 tons of coal, the Margaret sailed from Lydney in November 1882, bound for Hayle in Cornwall. The crew included Richard Stamp, aged 45 years old, as Master (manager and owner) and two of his sons, Jesse aged 11 and Thomas aged 14.

Carrying around 140 tons of coal, the Margaret sailed from Lydney in November 1882, bound for Hayle in Cornwall. The crew included Richard Stamp, aged 45 years old, as Master (manager and owner) and two of his sons, Jesse aged 11 and Thomas aged 14.

Margaret had been built in Gloucester in 1808 and is variously described as a Trow or a Ketch. Running down the Bristol Channel. the Margaret ran into heavy weather on the night of the 12/13th November. At 1am, just after passing Trevose Head, Richard Stamp was washed off the deck where he had been steering. The state of the sea made it impossible to turn the boat to attempt a rescue and his sons watched him drown.

Jesse Stamp became owner until he sold Margaret to Richard Hillman of Epney.

Thomas Stamp continued a career at sea. In 1918 he was serving on the Olwen a three masted vessel built in Ardrossan in Scotland. In June 1918, the Olwen loaded coal in Swansea for a voyage to Cherbourg. She left Swansea with a crew of seven including royal naval reservists manning guns. On the 9th of June she was reported missing and has never been seen again.

Thomas Stamp aged 50 was lost with his 16-year-old son Richard who had been signed on as cook. Also lost on the Olwen was Felix Tom Camm aged 29 from Epney.

1900 the voyage of the Excelsior

The Excelsior was a Jersey Vessel built in 1875. In 1900 she was owned in Bridgwater and captained by William Hawker of Saul, Gloucestershire. She sailed from Cardiff for Cork with coal. Initially ships followed the Welsh coast till they reached the ‘Smalls’ islands off Milford Haven. Here sailing ships crossed the Irish Sea to the Irish Coast. William Hawker was swept from the tiller by a freak wave and lost as the boat could not turn back because of damage. She was eventually intercepted by the Austrian steamship, the Rubino, who took her in tow. She then went all the way to Greenock in Scotland.

The Excelsior was a Jersey Vessel built in 1875. In 1900 she was owned in Bridgwater and captained by William Hawker of Saul, Gloucestershire. She sailed from Cardiff for Cork with coal. Initially ships followed the Welsh coast till they reached the ‘Smalls’ islands off Milford Haven. Here sailing ships crossed the Irish Sea to the Irish Coast. William Hawker was swept from the tiller by a freak wave and lost as the boat could not turn back because of damage. She was eventually intercepted by the Austrian steamship, the Rubino, who took her in tow. She then went all the way to Greenock in Scotland.

The Excelsior was owned in Gloucester from 1902 and became a barge in later life. Her remains are still in Sandy Bay, Somerset.

Ship building

Over 80 ships were built in Gloucester, many more around the county on river banks and in shipyards. The Hipwood family owned the yard above by Westgate Bridge in Gloucester. The family also ran a yard on Alney Island near the ‘Black Bridge’, the railway bridge on the line to Chepstow.

Over 80 ships were built in Gloucester, many more around the county on river banks and in shipyards. The Hipwood family owned the yard above by Westgate Bridge in Gloucester. The family also ran a yard on Alney Island near the ‘Black Bridge’, the railway bridge on the line to Chepstow.

Boat building started in the docks from around 1815 and the last boat was built 50 years later. The ‘La Belle Marie’, a small steam ship, was the last packet boat serving Brockweir, just before World War 1.

Pickersgill and Miller launched a series of boats built on the open land at Berry Close before the large dry dock and Alexandra warehouse were built.

Brockweir Port and Shipyard

Brockweir on the River Wye was the highest point that sea going ships could usually reach on a high tide. It had a small quay where cargoes were passed to smaller upriver boats to carry goods to Hereford and Monmouth. Until the early 1900’s there was only a ford to connect the village to the road and railway on the Monmouthshire bank.

Brockweir on the River Wye was the highest point that sea going ships could usually reach on a high tide. It had a small quay where cargoes were passed to smaller upriver boats to carry goods to Hereford and Monmouth. Until the early 1900’s there was only a ford to connect the village to the road and railway on the Monmouthshire bank.

The bridge now occupies the space where 14 ships were built between 1797 and 1869. Boats continued to be repaired up until the First World War.

At least 16 other ships were built on the banks of the River Wye on the Gloucestershire bank.

Framilode Passage Inn and boatyard

On the river bank at Framilode, there were 14 ships built between 1827-1872 by a number of different partnerships including John Powell, Henry Davis, Esaias Woore, Edward Rowles, James Nurse, Ezra Gardiner, Benjamin Gardiner.

On the river bank at Framilode, there were 14 ships built between 1827-1872 by a number of different partnerships including John Powell, Henry Davis, Esaias Woore, Edward Rowles, James Nurse, Ezra Gardiner, Benjamin Gardiner.

As a river side community between 5 and 10 % of the population worked in the maritime industries. The majority worked in farming. The Passage Inn was the base for the ferry crossing to the Forest of Dean shore. Further up the bank was the entrance to the Stroudwater Navigation. Framilode was famous for its annual regatta.

Canal Ironworks, Thrupp near Stroud

Between 1885 and 1934 nearly 300 vessels were built by Edwin Gardener and then Abdela and Mitchell in the Thrupp area on the Thames and Severn Canal. The majority were craft for the Amazon and other South American rivers. The Far East was also served and some boats were built for English firms. Boats that were too large to travel over the canal for export were built, numbered and then broken down and sent abroad for rebuilding.

Between 1885 and 1934 nearly 300 vessels were built by Edwin Gardener and then Abdela and Mitchell in the Thrupp area on the Thames and Severn Canal. The majority were craft for the Amazon and other South American rivers. The Far East was also served and some boats were built for English firms. Boats that were too large to travel over the canal for export were built, numbered and then broken down and sent abroad for rebuilding.

This image shows the Lotus, built by Abdela and Mitchell in 1904.

Cargoes

The major cargo imported via Gloucester and its ship canal was grain, of all kinds. At its peak there were three corn mills in the docks and several producers of cattle food. Ships arrived with the cargoes loose in the hold and gangs of men went into the hold to shovel grain into sacks. A sailing ship with 600 tons would require 6000 sacks. The majority of workers went from ship to ship. There were very few regular jobs.

The major cargo imported via Gloucester and its ship canal was grain, of all kinds. At its peak there were three corn mills in the docks and several producers of cattle food. Ships arrived with the cargoes loose in the hold and gangs of men went into the hold to shovel grain into sacks. A sailing ship with 600 tons would require 6000 sacks. The majority of workers went from ship to ship. There were very few regular jobs.

Timber porters

Timber porters with their shoulder pads.

The second biggest import was timber which came initially from the north of Russia and the Baltic. Gloucester industries like the Carriage and Wagon works used timber for the construction of railway vehicles. Timber was used for packaging and a lot went up the river to Worcester for Cadburys. Gloucester was also a centre for railway sleeper production as the rail network spread across the country in the 1840’s and 1850’s.

Salt

Worcestershire Salt was the biggest export from Gloucester. It was brought by narrowboat and rail to the Victoria Basin where it was loaded. Much of the salt went to Ireland where it was used to salt fish and in bacon factories. The first export from Gloucester in 1827 was salt for the fishing industry in Canada.

Worcestershire Salt was the biggest export from Gloucester. It was brought by narrowboat and rail to the Victoria Basin where it was loaded. Much of the salt went to Ireland where it was used to salt fish and in bacon factories. The first export from Gloucester in 1827 was salt for the fishing industry in Canada.

There was a proposal in the 1840’s that salt would be pumped to a processing factory in Gloucester to supply the majority of India’s needs. That never happened.

Coal

Gloucestershire’s major export was coal from the Forest of Dean. From 1809 tramways linked the pits to the river Severn and new docks were built at Bullo Pill and Lydney.

Gloucestershire’s major export was coal from the Forest of Dean. From 1809 tramways linked the pits to the river Severn and new docks were built at Bullo Pill and Lydney.

The Lydney canal linked the Forest of Dean industry. The Severn and Wye tramroad to the river, reopened Lydney’s earlier connection to the sea which had silted up. The outer harbour was open in 1821 and continued to develop. Coal tips lined the banks of the harbour and canal.

Sharpness Docks

In 1874 new docks opened at Sharpness. The ship canal had been designed for sailing ships. By 1874 there were many steamships in operation and they were both larger and a different shape which made the canal difficult to navigate. The new dock dealt in much the same business in Gloucester but in 1879 the Severn Railway Bridge opened, bringing Forest of Dean coal to Sharpness.

In 1874 new docks opened at Sharpness. The ship canal had been designed for sailing ships. By 1874 there were many steamships in operation and they were both larger and a different shape which made the canal difficult to navigate. The new dock dealt in much the same business in Gloucester but in 1879 the Severn Railway Bridge opened, bringing Forest of Dean coal to Sharpness.

Sharpness Docks are the last commercial port in the county still working.

Gloucester Docks

Gloucester Docks also handled coal brought down river from Worcestershire and Staffordshire which was taken to Cheltenham by horse drawn tramroad and later by the steam railway. Much of the coal handling was done in the barge arm.

Gloucester Docks also handled coal brought down river from Worcestershire and Staffordshire which was taken to Cheltenham by horse drawn tramroad and later by the steam railway. Much of the coal handling was done in the barge arm.

It had been hoped that Gloucester would become an exporting port and the Forest of Dean railway put two hydraulic coal lifts on Llanthony Quay. They were removed after a few years when the trade failed to grow.

Corn milling

A major industry in the docks was corn milling. The last company making flour closed in 1994 at the city mills. Albert Warehouse became a flour mill in 1869 and worked for nearly 100 years, across the dock. The St Owen’s Mill was next to the small dry dock.

A major industry in the docks was corn milling. The last company making flour closed in 1994 at the city mills. Albert Warehouse became a flour mill in 1869 and worked for nearly 100 years, across the dock. The St Owen’s Mill was next to the small dry dock.

Sack works were dotted round the docks, many in the Severn Road area. Jute imported from Ireland initially was made into millions of sacks which were in use up to the 1980’s. Sacks were repaired and cleaned in the docks using industrial scale vacuums and giant sewing machines.

Ships

The local sailing boat of the River Severn is the Trow. These were simple upriver barges or frigates, and boats that traded to Bristol with a single mast and canvas cover over the hold. Larger trows traded within the Bristol Channel and more adventurous owners went further afield. The River Wye also had trows.

The local sailing boat of the River Severn is the Trow. These were simple upriver barges or frigates, and boats that traded to Bristol with a single mast and canvas cover over the hold. Larger trows traded within the Bristol Channel and more adventurous owners went further afield. The River Wye also had trows.

Most of these vessels are described as working in the ‘River trade' which are the rivers and the Bristol Channel behind the Holme Islands which lie off Weston Super Mare. Most boats in the river trade would travel to ports in South Wales but Bristol was the major port.

The tall ship 'The Viking' enters Sharpness Docks in 1937 having sailed from Australia, the last big sailing ship to trade into the docks. She could carry 4000 tons of grain. She is rigged as a Barque. Ships going to Gloucester could carry a maximum of about 900 tons so they always unloaded part of the cargo at a port in South Wales or Sharpness.

Ketches and Schooners

The Sloops and Trows were the local delivery ships for the county’s rivers. Ketches and Schooners carried the bulk of cargo in the ’Home Trade’. The ‘Home Trade’ were the routes round the coast of Great Britain and Ireland and the North Sea coast of Europe from France to Germany.

The Sloops and Trows were the local delivery ships for the county’s rivers. Ketches and Schooners carried the bulk of cargo in the ’Home Trade’. The ‘Home Trade’ were the routes round the coast of Great Britain and Ireland and the North Sea coast of Europe from France to Germany.

The Schooner Nellie Fleming seen leaving Lydney will be carrying coal probably back to her home port of Youghal in Eire. She was lost with all hands in the Bristol Channel in 1936.

Tankers

From the 1920’s petroleum products became an important trade on the canal. Gloucester Worcester and Stourport all had storage tanks and different sized tankers served them.

From the 1920’s petroleum products became an important trade on the canal. Gloucester Worcester and Stourport all had storage tanks and different sized tankers served them.

The Wastdale H was built at Sharpness Shipyard in 1951. She was lost in an accident in October 1960 when she and the Arkendale collided off Sharpness and were carried onto the Severn Railway Bridge by the tide. Two spans of the bridge were brought down and a spark exploded the Wastdale’s cargo of petroleum spirit. Five of the eight crew on the two vessels were lost in the fire on the river.

The canal and River Severn had been busy with the petrol tankers up to the mid 1960’s but then pipelines opened and that trade disappeared. From the 1950’s Gloucester and Sharpness attracted small ‘Dutch’ coasters as European countries modified after the Second World War.

The canal and River Severn had been busy with the petrol tankers up to the mid 1960’s but then pipelines opened and that trade disappeared. From the 1950’s Gloucester and Sharpness attracted small ‘Dutch’ coasters as European countries modified after the Second World War.

In 1966 the West Quay warehouses on the left of this picture were demolished for easier lorry access in Severn Road Gloucester.

Gloucester Pilots

This is the Pilot Cutter 'Alaska', one of the craft used by the Gloucester Pilots. These men were tasked with piloting - guiding ships - in the difficult tidal waters of the River Severn outside the entrance to the canal at Sharpness. In the early days of the canal, pilotage in the Bristol Channel was controlled from Bristol, but Gloucester became a separate pilotage authority in 1861. Each pilot owned or shared a sailing cutter in which to go seeking incoming ships needing guidance and some would sail well down the channel, hoping to meet a large ship that paid a high fee. To keep their knowledge up to date, each pilot was required to carry out regular surveys of the river at low tide. To distinguish which port they belonged to, each Gloucester cutter was required to have G&S displayed on its mainsail. Most of the pilots lived in the small hamlets near Sharpness.

Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury was the farthest inland port in Gloucestershire and had an advantage in that it almost straddled the confluence of the River Severn and the Warwickshire Avon, so was well placed to handle river traffic on both rivers, in both directions. This picture shows the basin known as the ‘Quay Pit’ on the Avon, looking south towards Tewkesbury Abbey. Shipping with outward bound cargos on the Old Avon turned right here to join the Severn, while local craft with cargoes to unload headed through the stone entrance walls seen here onto the Mill Avon and the town quays. Most of the craft serving or passing through Tewkesbury were Severn trows, local craft that over time evolved from a pure riverine boat to sea-going vessels capable of long-distance voyages.

Tewkesbury was the farthest inland port in Gloucestershire and had an advantage in that it almost straddled the confluence of the River Severn and the Warwickshire Avon, so was well placed to handle river traffic on both rivers, in both directions. This picture shows the basin known as the ‘Quay Pit’ on the Avon, looking south towards Tewkesbury Abbey. Shipping with outward bound cargos on the Old Avon turned right here to join the Severn, while local craft with cargoes to unload headed through the stone entrance walls seen here onto the Mill Avon and the town quays. Most of the craft serving or passing through Tewkesbury were Severn trows, local craft that over time evolved from a pure riverine boat to sea-going vessels capable of long-distance voyages.

King Road

The authority of the Gloucester-Sharpness ship canal included control over navigation up to Sharpness and an area of the River Severn called the King Road, which lay opposite the Bristol Avon where boats waited to come upriver to Sharpness. There were a number of mooring buoys that lay out in the King Road to help waiting ships and, in the photograph, staff are working on the huge mooring anchors which kept the buoys in position in the fierce tides.

The authority of the Gloucester-Sharpness ship canal included control over navigation up to Sharpness and an area of the River Severn called the King Road, which lay opposite the Bristol Avon where boats waited to come upriver to Sharpness. There were a number of mooring buoys that lay out in the King Road to help waiting ships and, in the photograph, staff are working on the huge mooring anchors which kept the buoys in position in the fierce tides.

Rail links and shipping

One of the reasons that Sharpness and Gloucester docks were so successful was because the local railway companies – The Great Western Railway and the Midland Railway – quickly built rail links to them. These were linked by the Low Level Bridge seen here with four Midland Railway wagons on it. These railway lines allowed imports to be distributed without first having to pass up the canal to Gloucester, while coal from the Forest of Dean came across the Severn Railway Bridge to provide an export cargo and also fuel for steamships. The warehouses seen here in the background on the left (south-east side ) were multi-storey buildings intended for storing grain. Each had steam-powered conveyors and elevators that moved the grain in bulk to the required floor.

Ferries

Split by the River Severn and its estuary, there were several crossing ferries in the county, including one (Aust-Beachley) that was deemed of national strategic importance. While most were eventually replaced by bridges, one that wasn’t was the Newnham ferry, which ran across the river to Arlingham. This ferry was first recorded in 1238 when the king granted the woman keeping the passage of Newnham an oak for building a boat (possibly on hearing about the birth of his son, the future Edward I). The ferry was used by foot passengers and livestock until after the Second World War when it ceased. In 1810 work commenced to replace the ferry with a tunnel, but this failed, as did a plan to bridge the river in 1842. Today all that remains are the groynes for the proposed bridge’s slipway.