Introduction

Kingsholm is arguably the most famous area in Gloucester, thanks to the presence of the city's beloved rugby team, the Cherry & Whites. However it has had a long history that goes back over one millenia. Come with us and explore it in this exhibition!

Bronze Age barbed & tanged flint arrowhead

An insight into the prehistory of the Kingsholm area is this barbed and tanged flint arrowhead. It was found in 1987 during archaeological excavations ahead of the building of the Richard Cound BMW car dealership on the corner of Kingsholm Road and Denmark Road. It dates from the Bronze Age, around 4000 years ago, and has a broken tip and barb, so was probably lost in a hunting expedition. It is currently the oldest archaeological find in Kingsholm.

Roman bone hair comb, late 4th century

The Romans arrived in the area some time after 49AD and built a Legionary fortress at Kingshom, although it was later abandoned in favour of a new fortress 1km to the south (which would later become Colonia Nervia Glevensium and then the city of Gloucester). The Kingsholm area subsequently became home to extensive roman cemeteries which were in use for some 300-400 years. Romans – and as time passed the Romano-British – took funerals extremely seriously and professional undertakers were available to organise the funeral, manage the rites and dispose of the body. Without the benefit of funeral rites, it was thought that the vagrant spirits of the dead would haunt the living. Both cremation and inhumation were practiced although the tradition of cremation remained predominant in Britain until the 3rd century. Although relatively few grave goods have been found in inhumation burials and cremations occasionally they are discovered. This exquisite Roman bone hair comb was found under the shoulder of a female burial during excavations on the site of the Richard Cound BMW dealership. The burial was dated to the late 4th century.

City of Gloucester inclosure map, 1799

By the 600s, Gloucester was under the control of the Hwicce (one of the Mercian tribes) and from this time an Anglo-Saxon great hall – described as a ‘palace’ – existed at Kingsholm. It is known that it had ancillary buildings (including a chapel) and by the time of Edward the Confessor, the ‘great hall of the Royal Manor at Kingsholm’ was a meeting place of the King’s Great Council - the Witanagemot - raising Gloucester’s status to that of Winchester and London. The early Norman kings also used it as a royal residence – at least until it was superseded by Gloucester Castle in the 1100s – and it seems certain that it was from here that William I ordered the Domesday Book. The exact location is not known with certainty although it is believed to be on or around Kingsholm Square, roughly on the fields numbered 122, 123, 134 and 129 on the 1799 inclosure map.

Grant to the Hospital of St. Bartholomew's Hospital of an acre of land, being the acre nearest the town in the 'cultura' near Chingesweia extending to Abbey garden, Newland

This grant of land dated to about 1220 is one of the earliest mentions of the name ‘Kingsholm’, albeit it in an early form, ‘Chingeshame’. It records the grant of 1 acre of land from Ralph Auenel (with the consent of his wife, Margaret) to the Hospital of St. Bartholomew. The land lay near the road leading from Gloucester to the King’s Hall, which was known as the ‘Kings way’ (Chingesweia) and the garden of St Peter’s Abbey, so probably lay around the Park Street/Hare Lane area. The grant was witnessed by eight men, Sir Roger Poer, knight; William of Habenhale; Walter Hatchet; Richard the Burgess of Gloucester; John of Gosedich, David Doning, William of Sanford and ‘Peter of Chingeshame’ – Peter of Kingsholm.

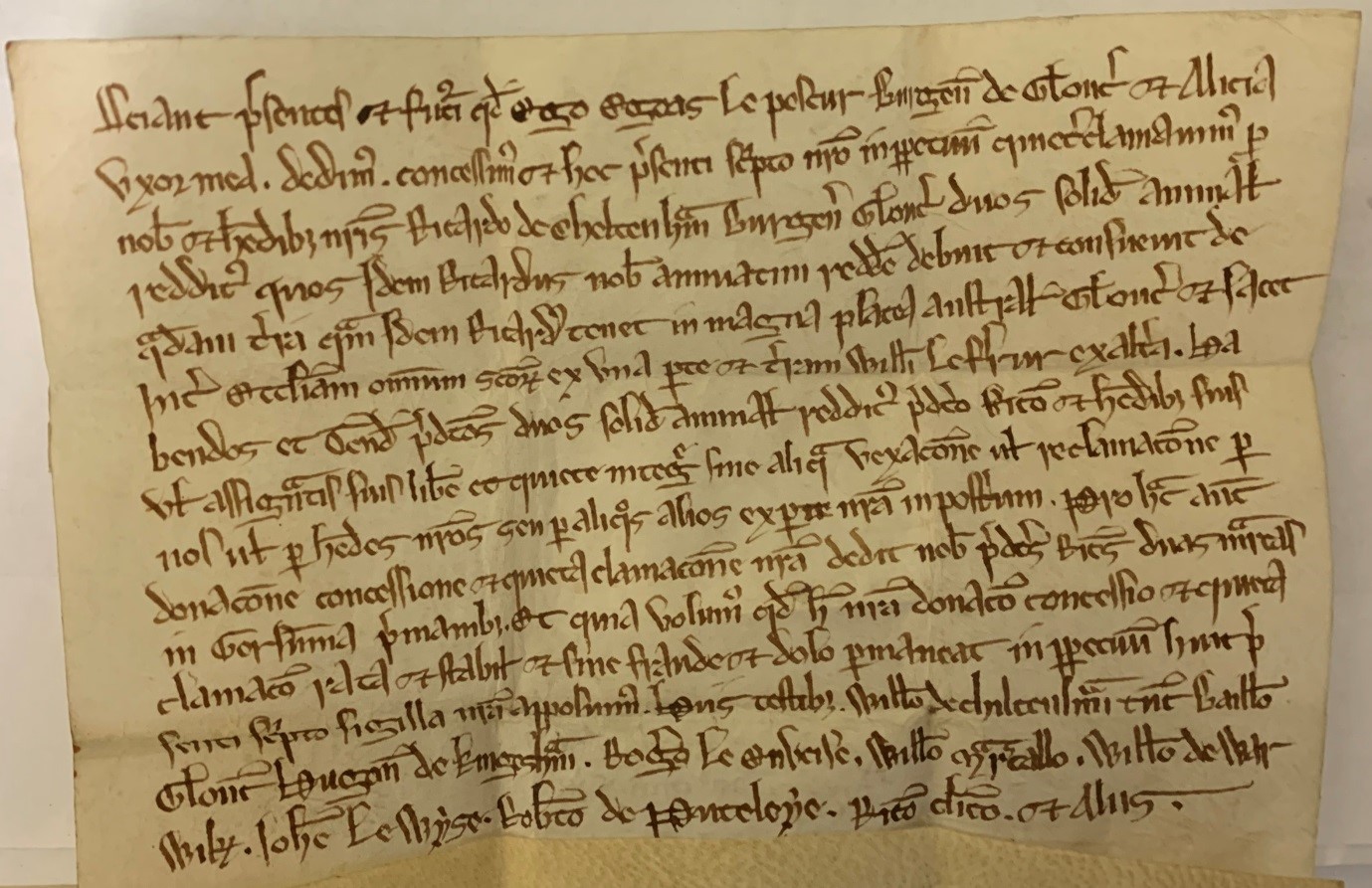

Grant of 2s of annual rent for the land held in the great south street between the church of All Saints and the land of William the Farrier

This grant, from Egeas the Fisher, burgess of Gloucester, and his wife Alice, to Richard of Chiltenham, burgess of Gloucester, is for 2s of annual rent that Egeas and Alice customarily paid to Richard. The grant is dated to about 1240 and shows an evolution of the name Kingsholm, from ‘Chingeshame’ to something more recognisable to us today – ‘Kingesham’, as it was witnessed by Hugh of Kingesham, whose name and place can be seen towards the left of line 14 . Coincidentally, it also shows an ancestor of the author, Robert de Puteleye.

Grant of four acres of arable land with a messuage at the Kingeshome lying in a field called ‘Pademeresfeltd’ between the land of Master Roger of Syston and the land of the brethren of the Hospital of St. Bartholomew

The first actual recorded exchange of land in Kingsholm we have took place about 1250, when William, son of William the Parmunter (tailor) of Kingeshome, granted 4 acres of arable land and a messuage to Herbert the Mercer, burgess of Gloucester. The land was in a field called ‘Pademeresfeltd’ and may have been in the south-west of Kingsholm as it lay next to land owned by St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. The field may have later been known as Pedmarshfield but the name seems to have survived to be recorded in a manorial survey of 1607, when it was listed as Pedmores Field.

Survey of all the manors, messuages, lands, etc. in Gloucestershire belonging to Sir William Cooke, Kt., and Lady Jocosa his wife By Ed Turner, esq, Steward, and Edward Eldred, gent., surveyor, 1607

There were once 2 manors in Kingsholm; Tuwell Manor, which was owned by St. Oswald’s Priory, and Kingsholm Manor, which was held by the king (via King’s Barton Manor). No records have survived for Tulwell Manor (which by the 1770s had shrunk to a small farm rented by the Dean of Gloucester), but records have survived for Kingsholm Manor, largely because it became part of the estate of Sir William Cooke of Highnam Court. This rather artistic page is the preamble of a survey of the manor in 1607, written in Latin as were all manorial records prior to 1733.

Example of Survey, 1607

The surveys usually all followed a set sequence, listing the fields and occupiers. They also include information about occupiers, field names, pasture and meadows. Of note in this image is that a difference is made between pastures (pastura) and meadows (pratum). Pasture is grazed but not cut, while meadows are cut for hay and may be grazed.

Court books: court baron

The archive of the Dean and Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral contains records of the Manor of Kingsholm, specifically the Court Book, court leet and view of frankpledge, 1783-1835. The functions of the court was threefold; to hold the ‘view of frankpledge’; to hear offences presented by the manorial jury and, to punish those found guilty (usually failure to carry out orders of the court). Like the surveys, they have a set sequence, starting with a preamble of the court meeting, the jurors (all residents of the manor) and then the business of the court. Frankpledge was a system of joint suretyship in England during the medieval period that saw the compulsory sharing of responsibility among the inhabitants in tithings (a tithing was a subdivision of a manor or parish) to keep the peace and adhere to orders issued by the manorial courts. The system declined over time as manors broke up and ultimately was superseded by parish constables operating under the justices of the peace. Technically, frankpledge is still in force in England and Wales with regards to riots, where inhabitants are responsible for paying for any damages incurred – albeit indirectly levied via the council tax in the relevant local authority area.

Example of typical Court Leet business, 8 October 1790

We present that the Ditch bounding Wm Wood’s ground adjoining on to Wallham Lane wants riding and that Wm Wood ought to rid the same. We therefore Order that he should rid the said Ditch by Christmas next under a pain of one shilling a lug for so much as shall be suffered to remain unrid after that time.

This image taken from the court leet volume shows a typical item of business handled by the court. In this instance, it records a ditch along Walham Lane that was overgrown and therefore, probably blocked, preventing water from draining into the Severn. The court ordered that William Wood, who occupied the land adjoining the lane was responsible for it and that he should clear the ditch (‘rid it’) by Christmas or pay a fine of 1 shilling per lug that was left uncleared. A lug – also known as a rod or perch – was 5.5 yards (5m) in length. At this time, a shilling was about £4 in modern money.

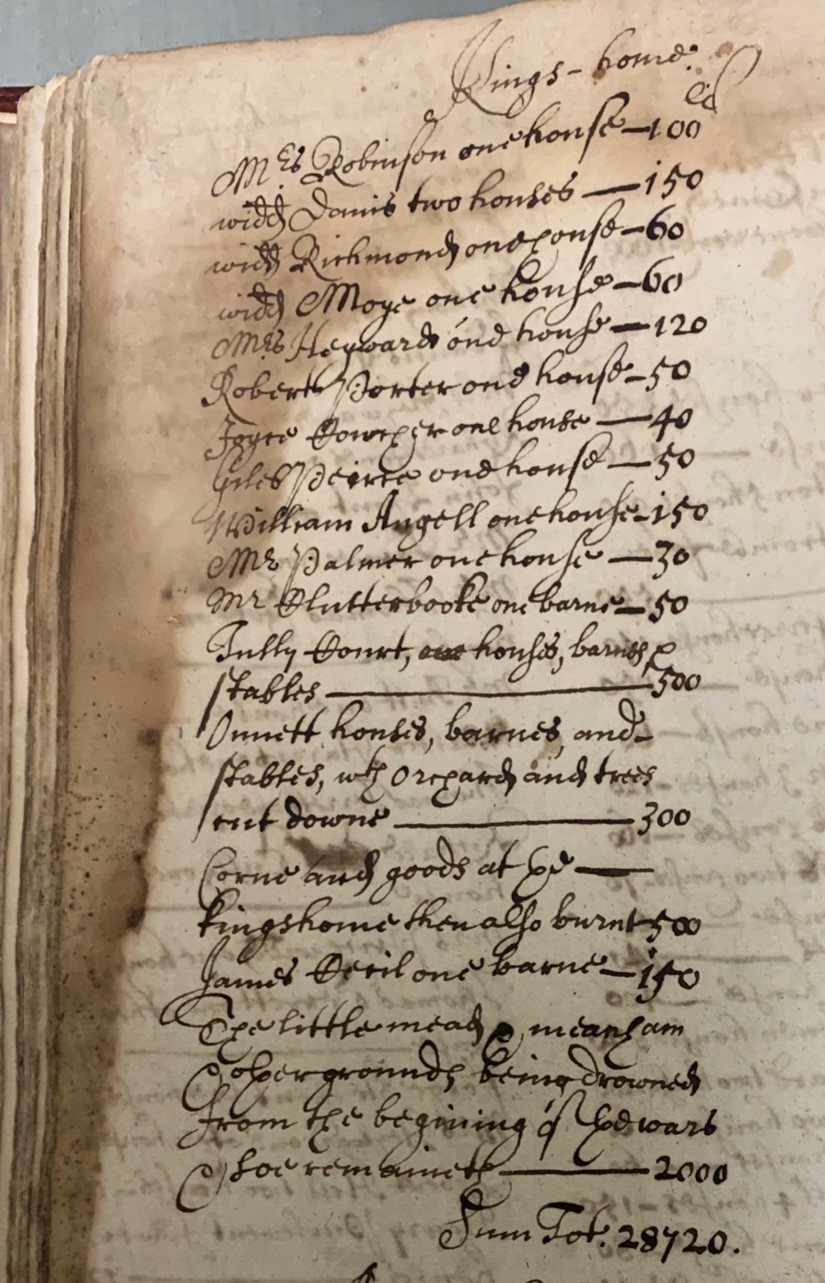

Borough of Gloucester order and letter book 1639-1661

In 1646, at the end of the First Civil War, the City Council undertook a Grand Inquest to determine the financial impact of the war on the city. The Mayor and Aldermen all agreed that in order to save the city from being taken by the King in the siege, the Governor and Council of War had no option but to destroy the suburbs and to flood the meadows on the north and north-west sides of the city. The inquest calculated that the overall losses that the city sustained came to £28,760 (just under £3 million today), but that other inhabitants suffered losses over that and ‘are in much want and misery'. This image, taken from the borough’s Order & Letter book, details the losses that occurred in Kingsholm, which amounted to 12 houses, 3 barns, 2 stables being destroyed or burnt plus orchards and trees being cut down and crops in barns being destroyed. While the cost of this was estimated to be £2,310, the damage to the fields – ‘for grounds being drowned’ – was put at £2,000, bringing the total for Kingsholm to £4,310 (about £446k today).

Plan of "City of Gloucester Denmark Road Estate"

From the 1840s onwards Kingsholm underwent fairly rapid development – from 30 houses in 1801 to 363 by 1861. Working-class terraces sprung up north-east of Alvin Street, along Worcester Parade, St. Mark Street and Edwy Parade, while town houses and villas were built around newly formed Kingsholm Square. In the 1880s, Dean’s Walk and Dean’s Way were built and soon after several new roads were formed between Kingsholm and Wotton, allowing more housing to be built. In 1874 the city boundary was extended Kingsholm became a ward within the city, ostensibly to allow more improvements, especially to the sewage system. This 1902 plan shows the proposed development along Denmark Road with the numbered plots that were to be sold. Prices ranged from 4s 6d to 5s 6d per square yard (about £18 to £23) with individual lots ranging from not less than £400 to £900 (£31,000 to £70,500). The plots on the left hand side were eventually to become Denmark Road High School which opened on the site in 1909, having moved from its original location of Mynd House, which lay closer to the city centre.

Application for a road rate

The Highways Act 1555 made parishes responsible for maintaining the roads in their area. As Kingsholm was not a parish at this time, when a group of inhabitants met to try and repair the local roads – which they presumably thought were in poor repair and detrimental to the area – they had to seek permission from the county’s Quarter Sessions to raise money to do so. This application to the Quarter Sessions comes from October 1772 and asks for permission to levy a rate of 3d in the pound for repairing the highways on inhabitants and landowners within the hamlet.

Cheltenham & Tewkesbury Turnpike Trust

The first Act for "repairing and widening the roads leading from the city of Gloucester towards Cheltenham and Tewkesbury" was passed in 1748 and was followed by several others. These were to be turnpike roads, where travellers were charged a toll to travel over the road, which was kept in good order (using money from the tolls for maintenance). Before 1823 (when Worcester Street was built), the road from Gloucester to Tewkesbury was via Hare Lane and then to Kingsholm, where it split into two: a low-route via Sandhurst, Wainlodes and Lower Lode, and a high-route via Longford, Norton and Coombe Hill. Like other turnpikes, operation of the actual gates was rented out to the highest bidder at auction, with the winner undertaking to pay an annual rent for 3 years and collect the tolls - anything the winner made over and above the rent was profit. This image is taken from the minute book of the trust for June 1778 and shows that Thomas Jones, innholder of Gloucester secured the 3 year contract for the Gloucester to Tewkesbury Turnpike after bidding to pay £154 a year. It is worth noting that by 1849, the auction winner was paying an annual rent of £405 indicating how much extra traffic was using the road.

Kingsholm Turnpike House

Familiar to all Kingsholm residents, this is the Old Turnpike House which is now a Grade II listed building. It was built on the Kingsholm road in 1822, to cover the Sandhurst and Longford routes. Prior to this toll house was nearer the Alvin Gate. The new toll house displaced the manorial stray animals pound which was moved to Gallows Lane (now known as Denmark Road). Tolls at the turnpike were as follows: horses were charged at ld each, except when they were drawing-a carriage, when they were charged at 3d. Cattle were charged at 10d per score, and calves, pigs and sheep at 5d per score. As on most other turnpike roads, wide wheeled wagons were generally charged less than those with narrow wheels, as the latter tended to cut into the road surface, while the wide wheeled waggons compressed the road and made it firmer. There were also certain exemptions from toll, including the local movement of animals and farm waggons, and waggons carrying road building materials. The Trust was wound up in 1871, when the County Council took over the highways.

Plan of Gloucester surveyed by the Ordnance Survey... for the Local Board of Health'

The 1850 Gloucester Board of Health map (signed by Andrew Beatty, Captain, Royal Engineers) shows a ‘Parchment Manufactory’ site on the corner of St. Catherine Street and Kingsholm Road/Worcester Street. This had tanning pits, a fleshing and splitting shops, a fitting & shaving shop and drying sheds. Very little is known about the company that operated it, although it had closed by 1870. It would have made the area rather unpleasant in terms of the environment, especially the smell!

Vinegar Works, Worcester Street, Gloucester: erection of offices

In 1870 John Stephens opened a vinegar & pickle factory in St Catherine’s Street on the site of the old parchment works. By 1881, it employed 30 men and 80 women but by 1901, over 400 were being employed. Around 1887, the site was rebuilt to plans designed by architects Moore & Maberly of Gloucester – this image shows the office block that was built for the firm. In 1901 the company was described as "purveyors, manufacturers, packers, bottlers, and manufacturers of or dealers in pickles, jams, marmalade, fruits, sauces, soup, jellies, food stuffs, provisions, confectionery etc.“ Stephens died in 1911 and in 1919, the company was to be voluntarily wound up to allow a reconstruction, although it actually continued trading until at least 1935.

Alvin iron works

A pair of iron foundries once existed in Kingsholm; the Alvin Iron Works on Alvin Street (now Gloucestershire Heritage Hub), owned by Henry Smith Crump and in operation from around 1860 to 1930 and the Kingsholm Foundry on Sweetbriar Street/Foundry Street (the site is now Kingsholm Primary School) in the early 1830s until the 1940’s(?). Sadly relatively few archive records have survived for either firm. The Alvin Works specialised in agricultural equipment and it won many agricultural show medals during the 1870s and 1880s, before demand for metal during WW1 caused the eventual demise of the business. An iron plate from the company can be seen today on one of the static carriages at the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire Railway at Toddington.

Kingsholm Foundry stop tap cover on London Road

Opened around 1855 by J.M.Butt & Co (originally from Dudbridge, Stroud), the Kingsholm Foundry specialised in rainwater pipes, guttering, bollards, drain covers (of which many survive in Gloucester) and pillar boxes. By 1863 the company had a showroom in Market Parade to display agricultural ironmongery to farmers visiting the nearby cattle market. The firm remained family-owned until being sold to Alfred Danks Ltd in 1917 and in 1922, when the latter merged the GRCWW, the Kingsholm foundry closed. Some street furniture of this company can still be seen on the streets of Gloucester today.

Poster advertising sale of Wheeler’s Alvin Street nursery, 1853

Gloucester's growing population provided a ready market for produce and the rich, easy draining soils allowed for extensive market and nursery gardens to be established in the suburbs. The most well-known was that belonging to James Daniel Wheeler, who inherited his father’s business and had a nursery on Alvin Street (now Gloucestershire Heritage Hub). He was one of several Wheelers who were nurserymen and market gardeners and although space precludes a full account of the family and their businesses, a good introduction to the family and other gardeners can be found in Gloucester Gardeners 1650–1763 by Jan Broadway (Transactions of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society No. 131 (2013) – available to be viewed online at https://www.bgas.org.uk/resources/bgas-resources/search-past-transactions). The main unifying theme however was that as time passed, pressure on the nurseries increased as demand for land (for housing, roads and the railway) in Kingsholm grew and, one by one, as the area was developed, the nurseries (and allotments) closed.

WW2 Searchlight site on Kingsholm recreation ground

In February 1940, the Army requisitioned the Kingsholm recreation ground, initially for an AA battery, but this was changed to a searchlight. This plan shows the layout of the site which was fenced off to prevent public access (something the city council hadn’t realised would be the case). On-site, an air-raid shelter, 2 Nissen huts, a corrugated iron covered walkway, office and workshops were built together with a hard-standing for the actual searchlight (marked by the number ‘1’ on the plan). It was operated for the duration by the 68th Searchlight Regiment (1st Rifle Battalion, Monmouthshire Regiment). After the war, the Army returned the site to the City council, but only after they tried to sell the Nissen huts to the Council!

Warden's log books for post F6

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) had 2 posts in Kingsholm. This image, from ‘Post 6F’ – but listed as ‘F6’ – is an air raid damage report recording 40-50 incendiary bombs and 2 high explosive (H.E.) bombs that fell at 20.15 hours on 16th Jan 1941 on Kingsholm Road, Gloucester Rugby, Sebert Street and Sandhurst Road. The pair of unexploded bombs had fallen on St. Catherine’s Meadow and these would have been dealt with by the Army UXB squads. Given the date, we know that the bombs were dropped by stray Luftwaffe bombers from a Bristol raid. The log books not only record air raids (usually noting down the Air raid Yellow, Red and All Clear times) but also training exercises and maintenance schedules.

Kingsholm Tennis Club

Kingsholm Tennis Club was established in the 1890s and the club still plays on Kingsholm Square to day – although it is doubtful that the ladies have to play in long skirts!

Opening of new ground at Kingsholm, 1891

Gloucester Football Club was founded in September 1873 – it only later became Gloucester (Rugby) Football Club. Although Gloucester Rugby is now indelibly linked to Kingsholm (and vice-versa) the club did not move to the ground until 1891, having played its earlier games at the Spa Field in Gloucester. The first game at Kingsholm was played on Saturday 10th October 1891 and the rest is history! The best place to discover the history of the club is to visit the ‘Gloucester Rugby Heritage’ website: https://www.gloucesterrugbyheritage.org.uk/

Tender to graze sheep on the Kingsholm ground

This would never happen at the Kingsholm ground today – given the partial synthetic pitch – but in the early days at the Kingsholm ground, farmers were invited to tender to graze sheep on the pitch in the close season. Presumably sheep were permitted as they did little damage to the pitch, whereas cows or horses may have damaged it.

Gaudron’s balloon at Kingsholm rugby ground, 1895

On the August bank-holiday in 1895, Professor Gaudron, a French aeronaut, brought his hot-air balloon to Kingsholm for a 2-day August bank-holiday extravaganza. Though tethered to the ground, some 5000 citizens were able to make a captive ascent to around 700 feet (213m) and get a birds-eye view of the city and the surrounding countryside. The following day Gaudron offered a free, untethered, flight, although poor weather meant only the event organiser, Mr Macrea, could go. The balloon took off and eventually ended up near Chipping Norton!