Introduction

This exhibition looks at one of the most popular local history activities – researching the history of a house. Because this is such a huge subject, it can only briefly touch the surface and so we have tried to give a flavour of what can be useful and what found within the archives rather than a fully detailed ‘how to’ guide. There's lots of useful information in the "Researching" pages of our website. You could start by looking at the local history page. You might also be interested in this online talk on house history in our Secrets Revealed series.

Urban street names

Street and road names can sometimes hint at past use, especially in urban areas. Streets named after churches are not surprisingly usually close to a church – whether it is open or closed. Streets with ‘Albion’ in them are usually associated with a non-conformist church. Streets and areas named after the monastic orders – Greyfriars (Franciscan), Blackfriars (Dominicans) and Whitefriars (Carmelites) – are also fairly common in cities and towns. So-called ‘Gate’ streets, such as Southgate Street, are also common in towns and cities, and were named after cardinal gates (South, East, West, North) but others are also known – such as Spittalgate Lane in Cirencester (thought to be a derivation of ‘Hospital Gate’) or Alvin Gate in Gloucester – the ‘gate’ element of the name has now been lost but it is remembered in Alvin Street.

Gloucestershire Archives

Suburban street names

With suburban areas, names can be much more mixed and can be chosen for a wide variety of reasons. Frequently themes are used, especially when entire new estates are built. Things like cathedral cities, flowering shrubs, local places, poets, etc, are often chosen. As such they rarely betray any historical origins for individual buildings. This image shows part of the Benhall estate in Cheltenham, built in the late 1950s/early 1960s on what was Benhall Farm. As can be seen, many of the roads in the estate are named after villages in the surrounding Cotswold countryside. There is one exception, ‘Robert Burns Avenue’ (not shown here), which was named after the Scottish poet following complaints that he was not among the poets with roads named after them in the older St Mark's estate to the north, even though Burns had a personal link with Cheltenham (his sons retired to the town).

Know Your Place

Hulbert Crescent

There can be exceptions in suburban areas however! Hulbert Crescent is named after the last residents of Up Hatherley Farm, which was demolished c1985 to make way for Morrisons and the new estates on the southern edge of Cheltenham. However as far as can be ascertained it was never glebe (church) land, so Glebe Farm Court is an invented name. Responsibility for street naming and postal numbering of all streets usually lies with the local authority. There are various criteria to be observed in street naming and local authorities use Sections 17, 18 and 19 of the Public Health Act 1925 to control and oversee both street naming and numbering schemes quoting convenience and safety of the general public.

John Putley

Street numbering - No.1 Bays Hill Terrace/No. 29 St. Georges Road

House numbers cannot usually be relied upon to identify a property, especially older ones, as they often change over time. Today odd numbers tend to be on one side of a street and even numbers another – although in cul-de-sacs or ‘fill-ins’ numbering can be way more haphazard. In the 1800s it was common for numbers to proceed sequentially up one side of the road and down the other - when new houses were built, the numbering was redone from the first house! A typical example of renumbering is in these maps of Cheltenham where No. 1 Bays Hill Terrace is now No. 29 St. Georges Road.

Know Your Place

Deed of 1646/7 relating to 103 Westgate Street

The prime archival source for any house history will be the deeds of the property. They are legal documents and ‘belong’ to the property, so they can be found with the current owner, their solicitors or mortgage lender. Many deeds have been deposited in Gloucestershire Archives but unfortunately, deeds have not survived for every property and not every bundle of deeds is complete. HM Land Registry holds records about most property or land sold in England or Wales since 1993, including the title register, title plan, title summary and flood risk indicator. When properties that date before this are sold, they are now added onto the Register. Deeds provide lots of information including the names of those who owned or occupied the property at various time, the extent and boundaries of the property, the date of the building and subsequent additions and alterations (i.e., in such a phrase as ‘one messuage now divided into two tenements’). Some have a map or plan of the property showing its footprint and boundaries and they often contain miscellaneous information about the bordering properties.

Reference D381/5 Image courtesy of John Chandler

Detail of deed of 1646/7 relating to 103 Westgate Street

Deeds follow a set pattern and conveniently these sections are separated by a word or two in bold text as can be seen in the image above.

- Date – in Regnal years, i.e., this example reads ‘This Indenture made the two and twentieth day of January in the two and twentieth year of our Sovereign Lord Charles by the grace of God King of England Ireland France Scotland….’

- The Parties – can be multiple names; usually starts with ‘Between’ and typically states where the persons inhabited. This example reads ‘Between Samuel Nicholls in the Cittie of Gloucester in the Countie of the Citty of Gloucester, gent and Damaris Nicholes one of the daughters of John Deighton, gent…. ’

- The Property – typically starts with ‘All that’….

- Restrictions/qualifications – often relating to family arrangements, typically starts ‘And’….

Deeds can be quite lengthy documents and it is easy to get lost within them. One of the biggest obstacles can be the handwriting – which can be difficult to read and there are often some ‘odd’ letter forms (C’s and r’s) and spellings used which we are unfamiliar with today. However, there are things in the reader’s favour - most deeds and especially early deeds, were written by professional scribes/clerks – so the writing is generally consistent. Once you get your eye in, words become easier, especially as because of its location in the deed, you will have a fair idea of what the word is probably relating to, i.e., a name, a date, a place. There are also lots of good guides to reading old handwriting.

Reference D381/5. Image courtesy of John Chandler

Epitome of title

Often deeds can be altered, added to or new ones drawn up to reflect legal changes. As this typically adds more physical material to deeds – you can sometimes find an Epitome of Title document that summarises the existing deeds and their contents and any previous deeds. Occasionally this would result in the older deeds being destroyed (unless they find their way to an archive).

John Putley

Lease for 21 years, 1647

Perversely, as more people learned to read and write, the standard of handwriting dropped. Copy deeds – used as back-up copies for records – frequently display far worse handwriting, because usually the writers were not professional clerks. This deed is lease for a ‘messuage and appurtences’ called Ty Rees ap Howell ap Moris in Montgomeryshire. The handwriting is quite poor, although it is mostly readable with a little effort. Of interest is line 6 which lists ‘a fat goose and a couple of capons at the feast of the Nativity’ – reflecting a payment for a Christmas rent.

Reference D2153/3/61

Grant of land in Standish, around 1270

Early deeds are almost always written in Latin – so can be impossible to transcribe or read if you do not have any knowledge of the language. However, despite this, such documents were almost always written by professional clerks, so the hand is generally very good and regular and often names and places can be made out. This deed records a grant of land in Standish made between John de Colethrop of Standish and William de Colethrop, of Gloucester around 1270. Although you would need the services of a specialist to transcribe it fully, even if you cannot read Latin, you can still make some things out. This grant is not dated like a typical deed but on the first line, the name ‘Iohnes de colethrop’ can be made out on the left, as can the name ‘William de colethrop’ on the right. The boundary along one side of the land in question was a stream called ‘Turdlesbroc’. This is the sixth word in on line three. Although quite easily made out, it is best not to ask what flowed through this watercourse!

Reference D214/T30A/9

Gloucester Directory, 1873

Directories are another way to linking deeds, names and properties and are very useful for house history research. They are generally available in town and county editions, with the former usually being more comprehensive. Dates range from the 1850s (relatively few exist for before this date) but better coverage starts from about 1870 and continues into the 1970s. They also tend to have larger copy adverts – such as this one which shows an advert for Thomas Green, a trunk maker of 49 Westgate Street Gloucester. His entry in the main part of the directory is on the left.

Image courtesy of John Chandler

Will of Joan Paynter, 1667

Wills are excellent resources for house and property history as testators often bequeathed property and possessions in the house. This is the will of Joan Paynter, which was proved by the Diocese of Gloucester in 1667. She owned what is now 109-111 Westgate Street. On the fourteenth line on the far right, it records that ‘I give and devise all my great messuage or tenements with all thaappurtences and all houses, edifices, buildings, gardens, courts, backsides, and hereditaments thereunto belonging, lying & being within the said parish of St Nicholas within the said citty of Gloster now in my possession…’. Although wills can be very long winded, especially if there was lots of property and/or lots of bequeathments, they are fabulous resources. They are available to view on Ancestry.

Reference GDR/WILLS/1667/92

Inventory of Robert Alsopp of Litteton, Tormarton, 1663

If an inventory has survived, the goods and chattels can be itemised by named room. In this example, we have the following mentioned in the house:

- Hall

- Kitchen

- Buttery & Brewhouse

- Parlour

- Hall chamber

- Parlour chamber

- Two chambers over the kitchen

- [chamber] over the brewhouse

This not only gives you a lot of information about the dwelling, which can help towards it’s size and layout, but the contents can provide details about the owner’s life style which can bring the house’s history very much to life. They are available to view on Ancestry.

Reference GDR/INV/1663/265

Taxation – Overseers of the Poor

One important area to consider when researching house history is that of taxation records – which can be both local and national. Although many types of taxation records survive, the information they contain is very variable – sometimes they relate to property and sometimes occupiers or owners. The earliest useable source is the 1597 Poor Law Act which ordered the creation of the Overseers of the Poor, who were empowered to raise revenue by local rates. This example from the Thornbury overseers accounts for 1657 and shows the poor rate that was collected in the parish – although it just lists names and amounts – it does not give any details of the properties.

Reference D688/1

Assessed taxes for Eastleach Turville, 1805

It’s said that only two things are certain in life: death and taxes. This was certainly true in the Georgian period when ‘assessed taxes’, were introduced. This is the return for Eastleach Turville for 1804-5 and lists three assessed taxes: window tax, servants’ tax, and the four-wheel carriage tax. The window tax was in force from 1697-1851 and was charged at 2s per year, but at 10s for houses with 10 windows or over. It led to some windows being bricked up but not as many as we think, as some were built bricked-up for fashion (especially on large houses) or were blocked due to later alterations. This tax can certainly give you an idea of the size of the houses and its status, for a larger ‘posher’ house will have more windows than a small single cottage. The other two taxes shown here – the servants’ tax and the four-wheel carriage tax can also help in house history by giving you an idea of the status of the household. The servant’s tax was a progressive tax introduced in 1777 and wasn’t repealed until 1889. It was levied at £2 per head on male servants (i.e., butlers, footmen, valets, grooms, coachmen, gardeners, gamekeepers, and huntsmen) but in 1785 was extended to female servants. The Four-Wheel Carriage tax was imposed on anyone possessing a horse-drawn conveyance from 1747 until 1782 and was charged at £12 a carriage, although farm wagons and trade carts were exempted. The charge varied depending on the size, number of wheels and number of horses used. If you think these are bad – don’t forget you also had to pay tax on wine, silks, gold and silver thread, silver plate, horses, hats, salt, candles, leather, beer, soap, starch, and wig powder!

Reference D1070/VII/62

Land Tax for parish of Aldsworth, 1788

A land tax of some form has been in existence from 1693 up until 1963. The main series in Gloucestershire starts post 1775 and are arranged by hundred then by parish. The records are of use as they list both property owners (proprietors) and tenants, placing them in both a parish and a year, although they do not give any information on the properties other than the size or area. They are available on Ancestry and can be searched either for personal names or browsed by place. Various other land tax assessments have survived but are scattered throughout collections.

Reference Q/Rel/1/Brightwells Barrow 1788

Maps: Sevenhampton - official inclosure map

Maps are perhaps the quickest and easiest resources to use when researching house history. Digital versions of the most important maps for house history research can be found at the following online websites:

Know Your Place - West of England – www.kypwest.org.uk – a free to use comparative mapping site for Gloucestershire, allowing you to compare old and modern maps, including 1st, 2nd and 3rd edition OS maps, town maps, enclosure maps, tithe maps and many more.

National Library of Scotland - https://maps.nls.uk/ - a free to use site, which has digital copies of most OS maps in the UK.

This image shows a typical enclosure map. Most enclosures took place between 1750 and 1850 but continued into the 1900s (Elmstone Hardwicke wasn’t enclosed until 1918). These maps are usually the earliest available for any particular parish, especially rural ones. Most are large, coloured and show landowners and plot numbers. The accompanying award includes information about owners and tenants, the position and size of each allotment and physical features, roads, hedges, walls, wells, quarries – they are very long winded! While the maps are available on Know Your Place, the apportionments can be viewed on a stand-alone PC in the Heritage Hub.

Know Your Place (reference Q/RI/123)

Badgeworth and Shurdington tithe map, 1838

The Tithe Commutation Act 1836 ‘commuted’ all in kind tithes to a cash payment, creating tithe maps and apportionments to record this. Some parishes do not have them as private arrangements to pay the tithe in cash were already in place. Tithe maps vary in size, scale and accuracy but generally cover a whole parish showing roads, rivers and other major landmarks - individual fields or plots of land shown and numbered and names and field names are usually given as well. The numbers on the maps refer to information in the apportionments, which list the name of the landowner, the occupier, the land use and value, and how much was to be paid in tithes. Digital images of this map are available via the Know Your Place website (www.kypwest.org.uk). You can also access the tithe apportionment data online (https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/archives/finding-items-in-our-collections/tithe-apportionments-database/). If you need to read the full apportionment including its preamble, you can do this through The Genealogist website (www.thegenealogist.co.uk), available free onsite at Gloucestershire Archives.

Know Your Place

1909 Finance Act maps

These maps were created as part of Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909, which funded old age pensions and a Dreadnought battleship building programme to compete with Germany. The main purpose was to tax capital appreciation of property that was attributable to the site itself, i.e. excluding that arising from crops, buildings and improvements. For house history it is useful as it created property Valuation Books (aka Domesday Books) and, as seen here, OS 1:2,500 maps with individual hereditaments marked up in numbers and colours. The Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeology Society has created an excellent website for the Gloucestershire data at: www.glos1909survey.org.uk

Reference D2428/3/31/11

Sales particulars for Wyck Hill Estate, 1931

Sales particulars can be wonderful resources - if they exist. They tended to be created for larger properties and estates, especially when these were sold by auction. These tend to have attached plans and inventories. As many properties were sold more than once, multiple sales particulars for different dates can exist.

Reference SL/172

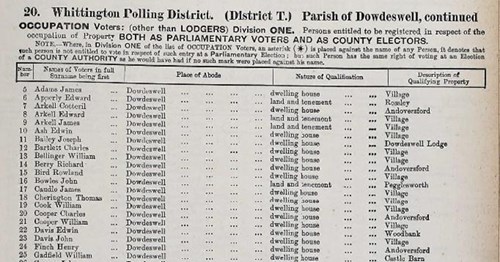

Electoral registers – section from 1889 Eastern (Cirencester) Division

Electoral registers start in 1832 and list people who were qualified to vote, at first by owning or renting property of sufficient value. Only from 1928, when women achieved equal voting rights, will all adult occupiers appear in these lists. They are divided into Parliamentary Divisions – which have changed over time – and typically provide a name and place of abode, and older registers may include a description of property and qualifications to vote. They can be searched on Ancestry.

Reference Q/Rer/1889/Eastern

Articles of agreement about building a house at Slaughter, 1656

This is the articles of agreement between Richard Whitmore of Lower Slaughter and Valentine Strong of Taynton, re building a house at Slaughter in 1656. It sets out everything necessary to build the house including walls, windows, chimneys (including a kitchen chimney). It required that Strong was to ‘find and bring into the place of building all such wall stones lime and morter as shall be necessary for the building of the said house’. The cost was £200…about £21k today

Reference D45/E17

Photograph of Old Smithy, Gotherington, around 1910

Photographs of properties can be invaluable in house history research, especially if they are dated, the location is given and any people show are named. This picture shows children outside the Old Smithy in Gotherington. It partly succeeds in that the location is identified and so is the subject – although we are left to guess which of the buildings is the Old Smithy – but sadly the children are not identified and there is no date.

Reference GPS/390/3