Will of Thomas Merrett, 1774

Prior to the 1830s, unless you were from a wealthy family, the only chance of education for children came via charity schools. These schools were funded by gifts (often left in wills) or endowments (income from investments). Charity schools often bought clothes for children to attend the school – blue coats were the norm (this was the colour of charity) and local examples include The Crypt School (1539), Sir Thomas’ Rich’s School (1666) and the Bisley Blue Coat School (1732). This is the will of Thomas Merrett of Tewkesbury, who died in 1724. After the usual preamble, in the third paragraph he instructed his executors to undertake the following:

..And as to the rest & residue of all and any personal & real estate I give & bequeath to my loving sisters Catherine Hartlebury and Barbara Leight, paying yearly fifty shillings per Annum to the use of the Charity School of Tewkesbury.

Document reference GDR/WILLS/1735/39

Watercolour elevation of Yate National School, 1853

Many schools were set up by voluntary subscription. Local wealthy patrons might pay for the building and running of a school at their own expense (i.e., Great Badminton C of E School by the Duke of Beaufort). Local people could also raise money to build a school, then pay an annual subscription to meet running costs (i.e., Newnham-on-Severn School). The ‘National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales’, usually just referred to as the ‘National Society’, was founded on 16 October 1811 to promote church schools and Christian education in line with the established church. It was strongly supported by the Anglican clergy, Oxford and Cambridge universities, and the established church, although the nonconformist Protestants were in strong opposition. The society’s aim was to establish a school in every parish in England and Wales. The schools it built were known as ‘National Schools’ – which were typically built adjacent to the local parish church and named after it. This is a watercolour painting of Yate National School, a typical example which is still extent and whose external appearance has changed little.

Document reference D2186/140

Photograph of Ebley British School. around 1880

The Society for Promoting the Lancasterian System for the Education of the Poor was formed in 1808 by Joseph Fox, William Allen and Samuel Whitbread. It was supported by several evangelical and non-conformist Christians, including William Wilberforce. In 1814, the Society was renamed the ‘British and Foreign School Society for the Education of the Labouring and Manufacturing Classes of Society of Every Religious Persuasion’. Based on non-sectarian principles, it opened many ‘British Schools’ and teacher training institutions and it was supported by several evangelical and non-conformist Christians. It was in active competition with the ‘National Schools’ although its schools were less numerous. Unlike the National Schools, it also established schools abroad, helping with the provision of staff and other support. Ebley British School was an imposing building that was built on land adjacent to Ebley Congregational Church in 1840. It was enlarged in 1844 and 1896, but numbers of pupils fell from 220 in 1885 to 142 in 1898, probably because of the opening of nearby Whiteshill school in 1887. The British schools – like the National Schools – were ultimately absorbed intop the state education system. The Ebley British school building closed in 1976 when a new school, Foxmoor County Primary School was opened and the staff and pupils were transferred there. Today the old school acts as Ebley chapel.

Document reference S68/4/14

Bisley School re-opening notice, 1872

Most voluntary schools charged a small weekly fee, known as ‘school pence’. The rate varied but was typically set at 3d (57p) for the first child, with reductions for others from the same family. At this time, a typical farm workers wage was 15 shillings a week (£34) – so school fees amounted to about 2% of their weekly income. This is a re-opening notice for Bibury School in 1872, after the school had closed for building work that extended its size to accommodate more pupils. The admission fees here are one child 2d, two children 3d and if more than two children 1d each (roughly 52p, 78p and 26p respectively). Perhaps the most difficult aspect for parents would be that the school requested prepayment at the start of term. Today the average term length is 13 weeks, so this would require payments of 2s 2d for one child, 3s 3d for two children and 1s 1d per child if more than two (provided our old money calculations are correct!).

Document reference P44/SC/1

Letter to Vicar of Coaley from T P Baily, 1882

This letter was sent to the Vicar of Berkeley by local farmer T. Baily in February 1882, after the former had sent a letter asking for money for a village school. Baily declined to contribute towards the maintenance of parish school funds and outlined the reasons in his letter:

‘Dear Sir

I received your letter and am sorry to inform you I do not agree with the agricultural labourers children being kept at school so many years. From my own experience, it makes them very idle, they do not as a rule take to work afterwards. I know of arguments for and against over education. I will give you a few shillings to give away at Christmas to a few deserving old people. I think that will do more good.

Yours faithfully

T.P. Baily’

Document reference SM/90/1

Twyning School Admission Register, 1914

Admission registers recorded the administrative details of a child in school. (They are not the daily attendance registers which are not generally retained long-term by schools or archives). The admission registers usually provide the following information: admission number, admission date, child’s full name, name of parent or guardian, address, religious exemptions, date of birth, child’s last school, date of leaving, the cause of leaving and lastly, any remarks. They can provide remarkable insights into village life. The two names at the bottom of this page of Twyning School’s admission register for the year 1914 records the names Johannes and Jacobus Bergamo – Belgian refugees from Antwerp, who'd fled the German invasion in WW1.

Document reference S343/2/2

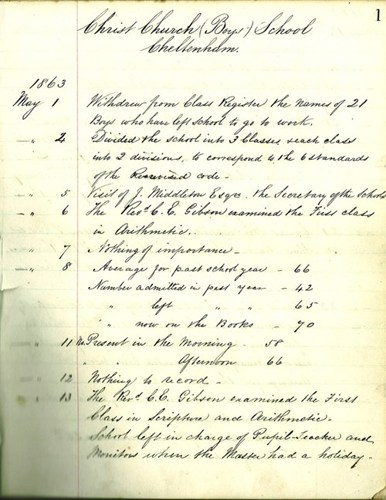

Logbook of Christ Church (Boys) School Cheltenham, 1863

School logbooks are the equivalent of nautical ship’s logs in that they record the day-to-day activity at a school. Logs books were usually pro-forma printed with margin, lines and page numbers. This is a typical log book page with dates given on the left hand side and comments on the right. School logbooks can be extremely interesting, as the information they contain can reveal all sorts of things. They can often seem obsessed with pupil attendance, Government inspections, Religious inspections and weather. Handwriting can be an issue! Another consideration is that some headteachers recorded everything – others recorded next to nothing!

Document reference S78/6/1/1

Truancy at Christ Church (Boys) School, Cheltenham, 1874

Log books always prominently feature pupil attendance. The reason was that prior to 1895 a school’s income was derived from the number of pupils attending therefore more pupils in school equalled more money. Pupils playing truant were fairly common and if caught they were punished – but in reality, there were numerous reasons why children didn’t attend school, especially in rural areas where farm help was often required. Some parents however were obviously concerned about their offspring playing truant – as this example from Christ Church School in Cheltenham in 1874 shows. Here, the mother of William George had requested that her son to be kept inside at dinner hour to prevent him from leaving school without authorisation.

Document reference S78/6/1/1

Aston-Sub-Edge School Religious Inspection, 1920

The Elementary Education Act 1970 set the legislative framework for schooling of all children between the ages of 5 and 13 in England and Wales. It was drafted by William Forster; a Liberal MP and was introduced on 17 February 1870 after campaigning by the National Education League. One of the reasons for its introduction was the perceived need for Britain to remain competitive in the world by being at the forefront of manufacture and education was seen to as a way to achieve it. However religious education became a contentious issue for the Act. Nonconformists forced a point that only non-denominational religious instruction should be given, as otherwise local ratepayers' money was effectively being spent on the Church of England. Despite protest from Anglican church leaders, the Government decided in favour of the non-conformist faiths and as a result, all state schools were non-denominational and in practice simply taught the Bible and a few hymns. However local Anglican vicars and diocesan inspectors could (and did) make regular visits and produced annual reports, such as the one copied into the logbook of Aston-Sub-Edge school in May 1920.

Document reference S27/1

Aston-Sub-Edge school Empire Day Celebrations, 1920

Empire Day was an annual celebration in most schools and was often heavy with Victorian self-congratulation. This page records the celebrations held at Aston-Sub-Edge in 1920.

Empire day was kept in the afternoon. The Rector spoke to the children & parishioners on the Empire as one of the steps in God’s plan for the union of all peoples through the League of Nations. The children sang patriotic songs, gave recitations, danced around the may pole, plaiting it in 7 ways. This was well done, the way in which the difficulties of varying sizes of children in a small school were got over was excellent. Mrs Warner is to be congratulated on the success of the celebration.

The celebration of Queen Victoria's birthday on May 24 was renamed Empire Day in 1902 after her death in 1901. In 1966 it was renamed Commonwealth Day and in 1977, the date was changed to the second Monday in March.

Document reference S27/1

Thunderbolt at Weston-sub-Edge School, 1910

Thunderstorms are often recorded in detail – primarily because school attendance frequently fell when they occurred. The logbook of Weston Sub-Edge school for 1910 records one notable thunderstorm or thunderbolt, which obviously terrified the children as several fell to the ground while others ran into the schoolroom. We presume that those that fell were just shocked rather than hit.

Document reference S360/2

Snow at Leighterton School

Snow and ice were other weather events that were recorded in detail in logbooks, especially in rural areas where they often seriously affected travel and therefore attendance. This extract from Leighterton Primary School records that on 29 Jan, the children from Tresham – a small village three miles to the west of Leighterton – were unable to get to school due to icy roads. A week later, on 5 Feb, a heavy snow fall forced the headmaster to close the school for three days. This was also a time when ‘snow fall’ probably meant a good 2ft/0.5m rather than the quantities we get today – and children were unable to walk to school through snowdrifts.

Document reference S56/1/1

Weather damage at Ampney Crucis School

The log book for Ampney Crucis school recorded the day when it flooded due to a thunderstorm – which also had a hailstorm that broke a school window!

Document reference S15/1/2

Children excused from Ampney Crucis school for farm work , 1915

Rural schools frequently allowed children to miss school to help with agricultural events such as harvest and haymaking, which in many cases were community events that whole villages partook in. This extract from the Ampney Crucis school logbook for 1915 records that the head has noted when a boy excused for hay making had returned to school. The use of child labour (mostly male) was doubly important at this time because most of the men had gone to war. The hay harvest was critical because it was crucial for the war effort. In WW1, the British Army used thousands of horses to serve alongside its soldiers. The bulk of these were draught horses switched from farm work or hauling buses to hauling heavy artillery guns or supply wagons, but small multi-purpose horses and ponies were used to carry food, shells, and ammunition. By 1917, the Army employed over 368,000 horses on the Western Front and these required food – as each horse required ten times the quantity that men needed, the supply of hay, oats and bran was one of the most important logistical operations of the entire war. It is estimated that around 1 million tons of horse feed was used in 1918 and hay made up approximately one-third of the total. It was transported in large bales and took up vast amounts of space – many cross-channel cargo-ships carried nothing but hay.

Document reference S15/1/2

Gleaning at Weston-sub-Edge, 1926

‘Gleaning’ – collecting leftover crops from farmers' fields after they have been harvested or where a crop was so poor that it wasn’t economically profitable to harvest was often practiced in poor rural areas and was crucial in helping families get enough food for winter. Some families also sold the gleanings they collected to raise income. This was possible because in the 1700s, gleaning was a legal right for "cottagers" or landless residents and in small villages, the sexton would often ring a church bell at eight o'clock in the morning and again at seven in the evening to tell the gleaners when to begin and end work. This legal right effectively ended after the Steel v Houghton case in 1788. This case became a landmark judgment in English law and is often considered to mark the modern legal understanding of private property rights. It came at a time when many parishes were affected by the enclosure movement and the subsequent wholesale transformation of property rights. Over the harvests of 1785-1787, conflict had been escalating between land owners and gleaners in the village of Timworth, Suffolk. In 1787, a villager called Mary Houghton gleaned on the farm of a wealthy land owner, James Steel, who subsequently sued her for trespass. The court sided with landlords and found against the gleaners' claims, rejecting arguments that it was common law, and determining that gleaning was a privilege and not a right, so the poor of a parish had no legal entitlement to glean and therefore it could be deemed trespass. Many saw this judgement as class oppression because of three arguments that the judgement used: firstly that the law should not turn acts of charity into legal obligation; secondly that granting a right to glean would "raise the insolence of the poor" and lastly that it was against the interests of the poor because by reducing the farmers' profits, it would reduce the rate payers’ capacity to contribute to the poor rates.

Document reference S360/2

Summer Holidays at Ampney Crucis School, 1913

Holidays are usually noted down in school log books – often with a sense of relief! They also record half-days given for various reasons. Summer holidays were often marked with some sort of celebration – as recorded here in the logbook of Ampney Crucis school which closed on 1 August 1913 and didn’t reopen until 15 September 1913. The end of the school year was celebrated with an ‘Annual School Treat’ in the afternoon. This was held at on the opposite side of the village to the school at Ampney Park, an impressive Grade II listed 16th century Manor House set in formal lakeside gardens and surrounded by wooded parkland. It seems likely that this treat was funded by the Squire, Frederick Cripps, owner of the manor house and the nearby Cirencester Brewery and the Cotswold Brewery.

Document reference S15/1/2

Holidays are usually noted down in school log books – often with a sense of relief! They also record half-days given for various reasons. Summer holidays were often marked with some sort of celebration – as recorded here in the logbook of Ampney Crucis school which closed on 1 August 1913 and didn’t reopen until 15 September 1913. The end of the school year was celebrated with an ‘Annual School Treat’ in the afternoon. This was held at on the opposite side of the village to the school at Ampney Park, an impressive Grade II listed 16th century Manor House set in formal lakeside gardens and surrounded by wooded parkland. It seems likely that this treat was funded by the Squire, Frederick Cripps, owner of the manor house and the nearby Cirencester Brewery and the Cotswold Brewery.

Document reference S15/1/2

Blackberry picking in WW1

During WW1, the government’s Food Production Department introduced a scheme inviting schools in six counties to let their pupils collect hedgerow fruit for money. The fruit was collected and processed into jam and preserves for the forces. Rural schools had a distinct advantage, but urban schools also took part, although some schools were more enthusiastic than others. This document is from the Gloucestershire County Council Education Committee records 1917-1919 and reports on the number of schools that took part in the scheme (223), the quantity of fruit collected (81 tons 19 cwt 14 lbs – approximately 82 metric tonnes), and the amount of money received from Government as a result (£1.270, around £38,000 today).

Document reference GCC/EDU/1/1/15

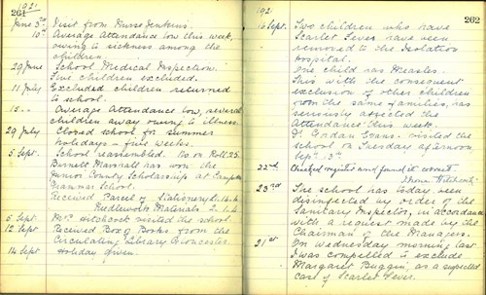

Sanitary inspection - Aston-sub-Edge School, 1921

School log books can reveal much about the general health of local populations and any epidemics that were passing through them. These pages from Aston-sub-Edge record a medical inspection – from which five children were excluded from the school for 2 weeks for an undisclosed illness – plus low attendance in July due to illness and an outbreak of scarlet fever on 16 September. The latter involved two children being sent to the isolation hospital. Scarlet fever is a disease caused by a streptococcus infection that was spread by coughing and sneezing, therefore schools were prime movers in spreading the disease. Before antibiotics were available, it was a leading cause of death in children. On the same day, a child with measles was also recorded, leading to the exclusion of other children in the same family. Five days later, another case of scarlet fever was recorded. This run of illness obviously worried the school managers for they requested a visit from the local Sanitary Inspector, who attended the school on 23 September, and ordered it to be disinfected.

Document reference S27/1

School death – Barnwood School, 1894

Very occasionally, deaths in school are recorded. On 8 October 1894 at Barnwood School, Charles Smith collapsed in a ‘fainting fit’. He was carried into the school by the Head, and his mother, the Vicar and a Doctor were sent for, but he died a few minutes later from heart failure. The school closed for the rest of the day.

Document reference S35/1

School dinners - St Michael's Church of England Primary School, Winterbourne, 1947

School dinners – loved or loathed, have left us with many memories and traditional ‘school dinner’ foods have become embedded in the national psyche. School food provision first became mandatory in 1906, when Parliament passed the Education Provision of Meals Act, which gave Local Education Authorities (LEAs) the role of providing free meals to schoolchildren in primary schools. Cooked from scratch on the premises, these dinners were intended to give children a hot, nutritious meal in the middle of the day. From 1944, a new National School Meals Policy was brought in, requiring LEAs to provide school food to everyone. Poorer children would still be provided with free food, while others could buy meals at a subsidised price. From then until the 1980s, school food is remembered with an equal mix of the loved (i.e., Hungarian goulash, minced beef pie, and chocolate crunch & pink custard) and the hated (i.e., liver & onions, mashed potato, overcooked cabbage, tapioca or sago (“frogspawn”) not to mention the universally despised prunes!). One highlight for many children was the provision of free milk, which was made obligatory until 1971 when Margaret Thatcher, education secretary in Edward Heath’s Conservative government, removed it for over-sevens at junior school. Although unpopular with most of the country (and leading to the unforgettable jibe “Thatcher, Thatcher, milk snatcher”), it became law in September. In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government ended entitlement to free meals for thousands of children and obliged local authorities to open up the provision of school meals to competitive tender. Although this reduced the cost of school meals provided by local authorities, it also caused a substantial decrease in the standard of school food. The 1980-2005 period is sometimes referred to as the ‘no nutrition standards era’ for school meals typified by the ‘Turkey Twizzler’.

Document reference S372/1/8/1

Aeroplane at Boxwell & Leighterton school, 1916

In 1916, the headmistress of Boxwell & Leighterton school recorded the entry shown below in her school logbook – not surprising as it would have been a highly unusual event. However within two years it became more common as in February 1918, the Australian Flying Corps opened a training airfield at Leighterton, so aeroplanes were seen aplenty. This can be contrasted with Rendcomb – in 1916, the Royal Flying Corps opened an airfield here on a scarp above the village school, but the headmaster never once mentioned an aeroplane or even the aerodrome!

Document reference S56/1/1

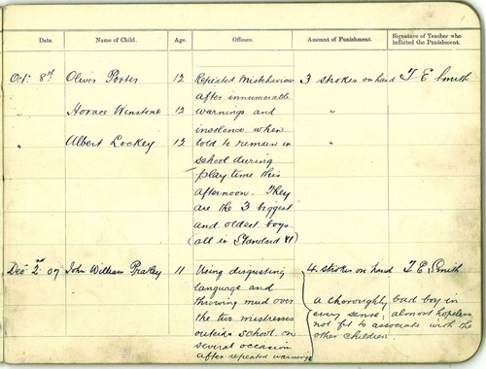

Punishment book

The Education (Administrative Procedures) Act of 1907 set up several systems for schools to follow. Many of these related to the health of children and among them was that every school had to have a Punishment Book in which all cases of corporal punishment were to be recorded. This is the cover of the punishment book for Tetbury School. Punishment books are closed for 100 years from the date of the last entry. In state-run schools, corporal punishment was outlawed by Parliament on 22 July 1986. In other private schools, it was banned in 1999 (England and Wales), 2000 (Scotland) and 2003 (Northern Ireland).

Document reference S328/2/4/5

Punishment book Great Rissington School, 1904

This page from the punishment book for Great Rissington School shows a somewhat atypical range of reasons for punishments. The first two boys, Ernest Hitter and James Hyatt, received 6 strokes of the cane on the buttocks and one on each hand for the strange offence of ‘Sheep driving without parents consent’. James Hyatt makes a second appearance, being punished when he ‘Knocked an apple out [of] a boys hand and started to eat the same’. The head teacher obviously wanted to clarify the offence, as he added, ‘Briefly a case of theft’.

Document reference S268/2

Punishment book Great Rissington School, 1907

This page shows the punishment meted out to John Pratley for ‘Using disgusting language and throwing mud over the two mistresses outside school on several occasions after repeated warnings’ – 4 stokes of the cane on each hand. However the head teacher has also added a note: ‘A thoroughly bad boy in every sense, almost hopeless, not fit to associate with the other children.’ Who’d be a teacher?

Document reference S268/2