Sweaty Toil and Sulphurous Airs: Gloucestershire’s Industrial Past

Gloucestershire has a long history of industrial activity. From an archival viewpoint, we have records of industry, industrial processes and industrialists from the 1400s onwards, and so this exhibition will look at all kinds of this heritage, where ‘industry’ is defined broadly as economic activity concerned with the processing of raw materials and manufacture of goods in factories or special places.

Gloucestershire has a long history of industrial activity. From an archival viewpoint, we have records of industry, industrial processes and industrialists from the 1400s onwards, and so this exhibition will look at all kinds of this heritage, where ‘industry’ is defined broadly as economic activity concerned with the processing of raw materials and manufacture of goods in factories or special places.

Scroll through the online exhibition to learn more about Gloucestershire's varied industrial history.

Upthrup Iron Works of Cam, agricultural engineers

GPS/69/25

By Victorian times, many agricultural engineering firms existed in the county. Most originated as blacksmiths, who would repair agricultural tools and make improvements to them. Like many small engineering firms, they would undertake any type of work – building and repairing carts and farm vehicles, making pumps and steam engines, repairing early cars, and making farm equipment. In addition, some became agricultural implement dealers and agents – such as Felix & William Lacey of Upthrup Iron Works of Cam, pictured here with his wife outside the premises on Upthorpe Lane.

Jack Cale, Basketmaker of Quedgeley

Gloucestershire Archives

Basketry was an enduring rural industry that had been practised since prehistory. At the end of the process were the basket weavers – these photographs shows Jack Cale making a wicker hamper. The Cale Family were noted basketmakers of Quedgeley, and they made numerous products from putchers for a fish weir, eel traps, and chairs.

Release from Cecily, relict of John of Cornwall and Christiana the Bellfounder to Brother John, Prior of the Hospital of St. Bartholomew of Gloucester, 1303

GBR/J1/773

Bell founding has been a Gloucester industry for over 1,000 years – the earliest known bell cast was in 890 AD in St. Oswald’s Priory. This release of 1303 names ‘Christiana the Bellfounder', daughter of 'Hugh the Bellfounder’ – this business was in lower Westgate Street in 1270, and by 1304 it was being run by his daughter. In the 1500s William Henshaw, five times Mayor of Gloucester, had established a bell foundry which gave its name to the (now lost) Bell Walk.

Contract of Abraham Rudhall, bellfounder, with Bibury churchwardens for recasting of bells, 1723

D269b/F84

The most famous bell founders in Gloucestershire were the Rudhalls, a family business in Gloucester, who between 1684 and 1835 cast more than 5,000 bells. The company was founded by Abraham Rudhall (1657–1736) who was described as the greatest bell-founder of his age and developed a method of tuning bells by turning on a lathe rather than the traditional chipping method with a chisel. Most of our records relating to Rudhall’s come from parish accounts – showing expenditure on their bells. This example is typical – an itemised receipt from Abraham Rudhall for casting 6 new bells for the parish of Bibury in 1723 – the bill coming to £56 12s (about £6,500 today). When Abraham died in 1735, the business continued in the family line but in 1815, John Rudhall (Abrahams’ great grandson) was declared bankrupt. The foundry was bought by Mears & Stainbank who owned the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and Rudhall’s formally closed in 1828.

Cheltenham Original Brewery Company’s New Brewery, Cheltenham

D8947

This is Cheltenham Original Brewery Company’s New Brewery in Cheltenham, rebuilt after the old premises burnt down in a fire. Commercial brewing began in monasteries where beer was brewed for the monks and as payments for lay staff - this shifted making of beer to men – it had previously been seen as ‘woman’s work’ and undertaken in private houses. Post-Reformation, common brewers began to appear and by the 1700s small industrial-scale breweries emerged, particularly in towns and cities, where they could capitalise on mass markets. Breweries were frequently taken over and/or merged by other brewers and this gradually led to just a few ‘super’ breweries appearing. Typical is the evolution of the Cheltenham Original Brewery, founded by J T Agg-Gardner in the High Street, Cheltenham in 1760. As time passed it took over or acquired at least 11 other brewers, including the Nailsworth Brewery; Wickwar Brewery, Wintle’s Brewery (Mitcheldean); Grafton Brewery (Cheltenham); Stow Brewery; Tayler's Brewery (Northleach); City Brewery, Sun Brewery (Gloucester); Bournestream Brewery (Wotton-under-Edge); Arnold Perrett & Co. Ltd (Wickwar) and Godsell & Sons Limited. In 1946, it changed its name to Cheltenham & Hereford Breweries then was taken over by Cheltenham Brewery Holdings Ltd, acquiring Stroud Brewery in 1958. In 1961, its name changed to West Country Breweries Ltd, then to West Country Brewery Holdings Ltd before being acquired by Whitbread in 1963 – who ceased brewing on the Cheltenham site in 1998.

Walham Brick Works & Barnwood Brick Works, Gloucester

1881 First Edition OS map reproduced with the acknowledgement of the Ordnance Survey

Brickmaking in the county took place in the Vales of Bourton, Moreton, Evesham and Gloucester – typified by the Brockworth Brick Works and the Walham Brick Works at Gloucester and the Stonehouse Brick & Tile Works – which contain Lias Group clays and the South Gloucestershire and Forest coalfields, which hold Carboniferous clays. In the 1910 edition of Kelly’s Directory 25 brickmaking companies were listed but there were many more smaller ng concerns – for example there were at least 15 smaller ones around Stroud, some of which only lasted for a few years. This map shows two brickworks situated at Gloucester - the Barnwood Brick Works on the west bank of the River Severn and the Walham Brick Works on Alney Island. It shows the numerous pits dug to extract clay that was used in the brickmaking process.

Coal mining – Freeminers’ drift mine in the Forest of Dean

D3921

Coal mining has been undertaken in Gloucestershire and South Gloucestershire since the medieval period. In the Forest, the Dean Forest Mines Act 1838, formed the basis of freemining law with miners registering to work a ‘gale’, which specified the place and mineral they could extract. The Act also confirmed the freeminers' exclusive rights to the minerals of the Forest but also allowed them to sell their gales to a non-freeminers – allowing commercial mines to open. Most mines were small, notoriously cramped drift mines, worked by just 1 or 2 men and typically had imaginative unusual names, such as ‘Strip and At It’, ‘Gentleman Colliers’ or ‘Rain Proof’.

Cannop Colliery, Forest of Dean, 1932

D7837/1

As well as drift mines, over 15 deep mines were opened in the Forest of Dean – this is Cannop Colliery in 1932 (now the Forest of Dean Cycle Centre) and it was Dean’s largest. It opened in 1912, and by 1930 employed 1,000 men, extracting 1,000 tons of coal a day (plus pumping 3 million gallons of water a day out!). When coal was nationalized in 1947, British Coal took over the deep mine collieries in the Forest, but not the small gale drift mines worked by freeminers. Cannop closed in 1960 (the cost of pumping water a major factor) and the last deep mine in the Forest, Northern United Collery, closed 5 years later on Christmas Day 1965.

Frog Lane Colliery, Coalpit Heath, South Gloucestershire

South Gloucestershire Council, courtesy Anne Matson

For a brief time, more coal was being extracted from the pits in South Gloucestershire than in the Forest. This is Frog Lane Colliery, which had a century of continuous productive life, being sunk in 1853, and not closing until 1963 – the last deep mine to shut near Bristol. Its workings were at a depth of 200m (660ft) and it had two shafts (one for pumping and one for winding). The remains of the South Gloucestershire coalfield industry cover a vast area of the ‘county’, including Bitton, Coalpit Heath, Cromhall, Downend, Easton, Frampton Cotterell, Hanham, Keynsham, Kingswood, Mangotsfield, Oldland, Pucklechurch, Rangeworthy, Siston, Stapleton, Warmley, Westerleigh and Yate. Though little remains above ground, more than 1000 mine entry-points and 42 coal seams are in the area, and most were worked for the extraction of coal between the 1870s and 1920s.

Frampton Cotterell Iron Mine, South Gloucestershire

SGC/4/1/2

The largest iron ore deposits in the county are in the Forest of Dean. It was extracted from limestone outcrops by surface workings, known as scowles. These have been exploited from Roman times onwards, and supplied blast furnaces in the Forest, Herefordshire and Monmouthshire until the 1600s when the deposits became commercially exhausted. However, the same geological conditions that created the iron ore to the west of the Severn Estuary also created iron ore reserves in the east, in the South Gloucestershire. This plan shows the approximate extent of the underground workings of Frampton Cotterell Iron Mine.

Crane Quarry (?), Minchinhampton.

D9746/1/2/111

There are – or were – quarries all over Gloucestershire, extracting rock, gravels and minerals. Many of these were small, short-lived concerns, used to extract stone for farm buildings – after which they were abandoned and usually left to slowly be reclaimed by nature. This image shows a deep quarry on Minchinhampton Common. It is possibly Crane Quarry, so called because there was a large crane installed – which may have run on the tracks seen here. The quarry was used to extract Cotswold stone but today it has been totally filled in and there is no trace of it on the surface.

Henry Workman’s Saw Mills, Woodchester, 1930/1

GPS/375/110

Woodland and most forests are planted as cash-crops, albeit over a long period and numerous sawmills existed in the county to process trees into timber. This wonderful image shows Henry Workman’s Timber Merchant sawmills at Woodchester in 1930/31. A traction engine is dead-centre while forwarders – specialist wagons used to carry felled tree trunks – can be seen on either side. These have horses attached and so are probably about to enter the yard, as horses were easier to manoeuvre than traction engines, which had relatively large turning circles. In the yard itself is a large steam-crane. This moved on a set of rails that ran throughout the yard to help shift tree trunks and sawn timber. This sawmill also had rail sidings (out of shot to the right), which connected the site to the Golden Valley Stroud-Swindon railway line.

Electricity - Arnold Perret & Company Brewery, Wickwar, c. 1881

1902 Second Edition OS map reproduced with the acknowledgement of the Ordnance Survey

The first place in the county to get electricity in the county was Wickwar and it was also ‘green’ electricity! During the winter of 1887-8, the Arnold Perrett & Co. Ltd brewery installed a hydroelectric plant to light the brewery (with 100 lamps), and the surplus electricity was sold to the Town Council. The electricity was generated by an overshot 36ft (11m) diameter waterwheel that drove an Elwell & Parker dynamo which ran at 550rpm. The waterwheel was powered by water taken from a reservoir to the east of the brewery, which was supplied with water from the Little Avon, as the lie of the land allowed the river water to flow into the reservoir via sluices. This provided the waterwheel with the head of water required to turn it at a speed to power the dynamo. Sadly, the OS grid cuts the brewery in half! Subsequently, electricity supply began in Cheltenham (1895), Gloucester (1900), Tewkesbury (1908), Cirencester (1912) and finally Stroud (1916).

Gloucester from Hempstead, undated painting.

Gloucestershire Archives

Glassmaking in Gloucestershire began in the 1500s and 1600s, with glasshouses at Taynton, Woodchester, Newnham and later, at Gloucester quay. These glassworks were mostly set-up by Huguenot glassmakers fleeing the continent. One reason for the trade coming to the county was that in 1615 wood was banned from being used in glassmaking (preserving it for naval shipbuilding) so the industry gravitated towards areas with coal. Glassmaking typically used ‘pot kilns’ which actually had three different furnaces – one holding a crucible to keep glass molten, one a ‘glory hole’ (used to reheat glass during working) and lastly a ‘lehr’ or ‘annealer’ used to slowly cool the glass. Glassmaking had begun in Gloucester by the early 1720s, with a large conical glasshouse at the quay and one north of the Foreign Bridge – in this painting, the large conical building seen here on the left was the top of the glass making pot kiln furnace. The site was making bottles, pickling and butter pots, and melon glasses but production ended in 1744.

'Court of Aldermen', order to John Tisley, pinmaker

GBR/G3/SO/1

One of the main trades in the city was pin making with pins being made by hand from the 1500s until into the 1800s. By 1735 Gloucester was seemingly the largest pin-making centre in Britain, employing 1,200 men, women and children – some early workers were paupers and orphans (essentially free-labour) ‘employed’ by pin maker John Tilsley via an agreement with the City Corporation. This entry in the Borough Court of Aldermen’s order book contains some details of the arrangement. In 1743 William Cowcher set-up a pin factory (now The Folk) and in 1853, this was taken over by the Birmingham firm Kirby Beard & Co, being known as Cowcher, Kirby, Beard & Tovey. This nationally important firm introduced a major advance in the early 1800’s when this firm began tentatively using machinery to make pins – firstly straightening and drawing the wire, then grinding the points. By the 1820s, this had matured and fully automatic pin-making machines – that could make 40-50 pins per minute – were in use.

Match drying, S J Moreland & Sons, c. 1960

D13085/2

There were several match factories in the county, but the most famous was Moreland’s. Samuel J. Moreland, son of a Stroud sawyer, was born in 1828 and in 1867, he moved to Gloucester opening the ‘Moreland Match Manufactory’ to make non-safety matches – the ‘England’s Glory’ brand. In 1913, after 46 years of operation, Moreland’s became a subsidiary of Bryant & May and by 1938 was wholly owned by them, remaining so until the site closed in 1976. This image shows a worker drying the matches after their heads had been dipped in the ‘pink stuff’ – this was a mix of phosphorus sesquisulfide, potassium chlorate with pink dye.

Lower Slaughter Corn mill

GPS/296/9

The Domesday Book records over 6,000 mills in England, and it is likely that there were more that were not recorded. Larger villages often had larger mills with complex water management systems. Bibury mill had a reservoir in Ablington, which fed the mill via a ¾ mile (1.2km) long leat, while Lower Slaughter – shown here – had a 1.3-acre (5,200 sq.m) mill pond. Many mills later installed steam engines (hence the chimney) primarily to act as auxiliary power sources to help mill corn in times of low water levels, but some also used them to pump water into their mill pond or mill leat to enable the waterwheel to function. Another reason was that it enabled the mill to grind corn faster to compete with steam powered mills.

Carpet loom machine shop, Champion & Hall Carpet Manufacturers, Dursley

GPS/124/34

The woollen trade was once the principal industry in the Stroud area, initially because of the availability of waterpower to drive mill machinery – though later steam power took over. Textile of cloth mills made cloth and related products – this image show carpet looms inside the mill of Champion and Hall Carpet Manufacturers in Dursley. Champion and Hall were originally a saddlery business but expanded into rope making before finally moving into cloth and carpet production. Gloucestershire was famous for its superfine broadcloth, most of which was intended for the overseas market.

Sheepscombe Flock Mill

D9746/1/13

Several different types of textile mills existed – including Fulling mills, Gigg mills, Flock mills and Shoddy mills. Externally, these mills were mostly undistinguishable from corn mills, but their internal machinery differed. Fulling mills cleaned and thickened the cloth by pounding it with heavy hammers, or fulling stocks. Gigg mills ran a type of raising machine that used racks of teasels to produce and raise a nap on cloth Flock mills used a large drum filled with iron spikes, which loosened and separated cloth fibres, to produce ‘flock’, while ‘shoddy’ mills were similar but used a mix of recycled wool and new wool to produce a cheaper end product. Both flock and shoddy was used for stuffing mattresses and upholstery.

In-Shire of Gloucester, 1624 showing windmills

GBR/Acc7380

Windmills were found where water gradients were too low to drive a water wheel and so were common in the Vale of Gloucester. This image shows part of the In-Shire of Gloucester, which was an area that lay outside the city boundary, but which was governed by the borough and its burgesses. Control of this area was removed at the Restoration, as part of the city’s punishment for supporting Parliament during the Civil Wars. The windmills shown here all appear to be post mill types, where the whole body of the mill that houses the milling machinery is mounted on a single central vertical post. The vertical post is in turn supported by four quarter bars, which act as struts to steady the central post. They were the earliest type of European windmill and first appear in England in the 1100s. They were superseded in the 1200s by tower mills – which in turn were replaced by smock mills in the 1600s.

Advert for N. J. Godwin Ltd’s Hercules Windpumps

Gloucestershire Countryside 1934 Vol.4 May-Jun

Windmills were also common on the high Cotswolds, where wind power was used to pump water up from boreholes to isolated farmsteads and for animals. Some of these were manufactured locally, like the ‘Hercules Oil Bath Windmill’ by Godwin Ltd of Quenington and similar ones are used today for electricity generation.

Fielding & Platt Engineers

D9746/2/364/22

Founded in 1866 by two Lancashire men, Samuel Fielding and James Platt, the company initially made small engineering machines and components. It soon branched out into larger items – including gas and oil engines, iron steam ships (one, the S.S. Sabrina, is still in use on the Thames) and a bridge across the Severn at Gloucester Docks (only replaced in 1962). In 1871, they began making the portable hydraulic riveting technology of Ralph Tweddell and quickly built a business exporting hydraulic machinery, in addition to various engines, worldwide. The firm was particularly noted for the quality and long life of their products and the care of their staff – it remained in business until 2000.

J. E. Thomas coal wagon, Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Company Ltd

D4791/16

Formed in in 1860, this company made goods wagons, passenger coaches, diesel multiple units, electric multiple units and various special-purpose vehicles. Its stock in trade were private owner coal wagons, like the one featured here, which were made for both local and national concerns. The company also supplied the original fleet of red trains for the Toronto Subway and rolling stock for the London Underground. In WW1 they made horse and railway ambulances, artillery limbers, aircraft wings and in WW2 they made Churchill tanks and pivoting sections for the Mulberry harbours. Post-war the company shrank, and manufacturing ceased in 1994.

Muir-Hill Loading Shovel and Dumping Tractor

D4557

Begun in the 1920s. Muir Hill (Engineers) Ltd was a general engineering firm based in Manchester. It specialised in products to expand the use of Fordson tractors (primarily bucket loaders) but in the 1930s they created the dumper truck. In 1959, they were taken over by the Winget Group and production moved to the former ‘GRCWC’ works in Gloucester, under the name E. Boydell Ltd but trading as "Muir-hill". Corporation games ensured they had many different owners over the years, including Babcock and Wilcox, Sanderson and others. Today they survive as Lloyd Loaders MH Ltd.

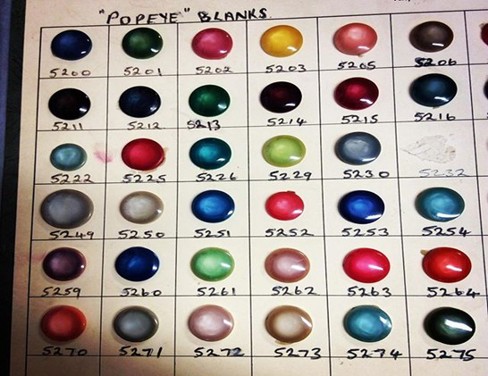

Erinoid Casein Popeye blanks

D4251/1

In 1908, a new plastic called ‘casein’ made from milk curd was invented by Latvian chemist Victor Schutz. Syrolit Ltd obtained a production licence and in 1911 moved from Middlesex to the old cloth mill at Lightpill in Stroud – as this was nearer to the Irish milk it used. Marketed as ‘Erinoid’, this casein plastic could be dyed in bright colours, could withstand washing, ironing and dry-cleaning solvents and so became popular for buttons and other household goods. Mostly superseded by oil-based plastics it is still made today on a small scale for high quality goods, though the Stroud factory closed in 1982.

Tupa steam launch, Abdela & Mitchell, 1911

D9746/2/351/11

Shipbuilding was a well-established industry in Gloucestershire from Tudor times onwards with numerous craft of all sizes initially being built on the estuary and riverbanks. One of the busiest firms was Edwin Clark & Co, who opened in 1884 at Hope Mill near Brimscombe and began building boats at the Canal Ironworks, on the Thames & Severn Canal. The firm specialised in prefabricated craft, making steamboats that were sent around the world. In 1896 Edwin Clark died, and the firm was subsequently purchased by Isaac J. Abdela (a shipping broker of Manchester) who was joined in partnership by Mitchell & Co (grey cloth merchants of Manchester). This unlikely partnership resulted in the largest shipbuilding concern in the county, eventually making well over 100 vessels, mostly small steamers and launches, many for overseas use. Shown here is the Tupa, which was typical of their output. She was a 20ft long single screw steam launch that was built between 1905-1911 for owners in Brazil.

Chalford Stick Company employees

D9746/2/38/6

In the valleys full of cloth and textile mills around Stroud, a thriving little industry sprang up around making walking sticks and umbrellas. These included the Chalford Stick Company Ltd and A. C. Harrison & Co. of Bliss Mills to name but two. This picture shows the employees of the former at the company’s premises at St. Mary’s Mill. About one-third of the workforce in this image are women, probably employed to undertake stitching on umbrellas.

Clog Makers at Colesbourne

Cheltenham Chronicle & Gloucestershire Graphic 5 December 1908

Some industries went on in the background with little or no record – this image records one of these – and it is a somewhat unlikely trade in Gloucestershire, clog sole making! Clog soles were typically made of soft, lightweight woods – such as alder, willow, birch, or sycamore. Alder grows well on land that is too wet for other trees and some land like this existed on the Colesbourne Estate, so alder in these places was plentiful. In 1908, Lord of the Manor of Colesbourne and owner of the estate Henry Elwes, invited four Cheshire clog sole makers onto the estate to see whether clog sole making was a viable proposition. It clearly was for between them the four men purchased 100 alder trees off the estate for £24 10s (about £1,920 today) and eventually from these trees they produced 622 pairs of clog soles, which they subsequently sold in Oldham! Unlike Dutch clogs, British clogs had wooden soles and leather uppers, which gave better comfort and a tighter fit for labourers. This little sideline for the estate may well have been repeated in later years, until the then current crop of alder had been exhausted.