Introduction

The census is one of the best resources for anyone interested in local and family history. Taken every 10 years, together they create a snapshot of history that we can look back into and interrogate. They allow us to delve farther than many other records as they provide details on family relationships, occupations, and other social settings such as habitations, farms, industry and more besides. This exhibition looks at some of these aspects and hopes to reveal just what you can find and how exciting it is. Unless indicated all the census images are courtesy of The National Archives and/or Family Search and partners (Ancestry/Findmypast).

The 1801 Census

Britain was a slow starter when it came to undertaking a census. The reason was that the government feared it would reveal the nation’s weakness to foreign enemies. However, this attitude changed in 1798, when the respected economist and demographer Thomas Malthus, published ‘An Essay on the Principle of Population or A view of its past and present effects on Human Happiness’. Malthus postulated that an increase in a nation's food production improved the well-being of the population, but it was only temporary, as it led to population growth, which in turn led to higher demand for food and lowered standards of living the until food supply was increased. Malthus argued that population growth in Britain would soon outstrip supplies of food and other resources, leading to famine, disease and ultimately, financial collapse, unrest, and revolution. Terrified by this potential outcome, the government decided to act, and the first census took place on 10 March 1801. The information was collected by the parish Overseers of the Poor, aided by parish constables and other officers of the peace. It revealed that the population was 8.9 million living in 1.8 million houses. This image shows the entry in the Ashleworth parish register:

March 10 – At a numbering of the Inhabitants of this parish taken by order of Government the numbers were as follows: Inhabited Houses 80 families 88 Uninhabited houses 5: Total males 237. Total females 239 together 476 Inhabitants: out of these 421 were employed in the business of Agriculture & 55 in Trade.

Enumerators' routes

The enumerators were free to collect census returns however they wanted although they did have to record the route that they took. This information was recorded at the start of each enumeration book in a box entitled ‘Description of Enumeration District’. Some routes are straightforward, but in rural areas the description might simply read ‘The whole of the parish of …’. This example for Bibury is typical and doesn’t really give the reader an idea of how the enumerator went around the parish.

Enumerators' routes – ‘All that part of….’

Some routes are clearer - this extract from the 1881 census for Coaley is for part of the village that lay ‘…on the Upper or Easterly side of a line drawn in a straight direction commencing at and including William Hills, Betworthy Farm House and from there to the boundary of the Parish of Frocester…’. Looking at this on a map such as the 1881 OS map – available to view on Know Your Place west (http://www.kypwest.org.uk/) – you can tell that this part of the census for Coaley only really covered the southerly part of the village.

1841 Census – Castle Barn, Dowdeswell

The 1841 census is considered the first modern census and the one that produced the earliest genealogically useful information. Enumeration forms were distributed to all households a couple of days before the census night (6 June 1841) and the completed forms were collected the next day. If the head of the house was illiterate or had any problems completing the form the enumerator would assist as much as necessary. The information from the individual forms was then copied into enumerators' books, which are the records we can view images of today. The information asked for included: Name of street, avenue, road, etc; House name or number, Surname of head of household, Name of persons who had spent the night in the household, Age, Sex, the Person’s occupation and, Where born. This column asked two questions: 1) whether born in same county, and 2) whether born in Scotland, Ireland, or Foreign Parts. Possible answers and abbreviations were: Yes (Y), No, (N), or Not Known (NK), while for the second part, abbreviations were used: Scotland (S), Ireland (I), and Foreign Parts (F). A major problem with the 1841 census is that it was written in pencil rather than pen so much of the data has faded.

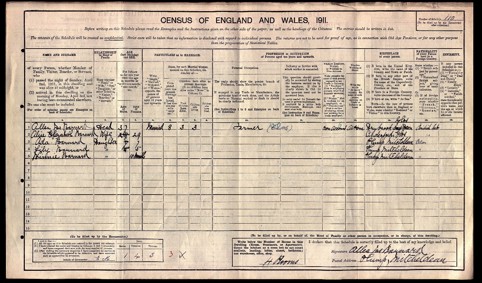

1911 Census – Castle Barn, Dowdeswell

The 1911 Census of England and Wales was taken on the night of Sunday, 2 April 1911. Every census tended to ask for more information than the previous one and in the 70 years since the 1841 census, this had expanded greatly. The 1911 census asked for the following details: name, relationship to head of family, age at last birthday, sex, marriage details (including number of children), occupation (for people aged 10 and over), birthplace, nationality, infirmity (deaf, blind, lunatic, etc.), postal address and military rank and unit if applicable. It also included so-called ‘fertility’ questions. These asked how long a present marriage had lasted, the number of children born alive to the present marriage (including children no longer living in the household) and number of children who had died. More detailed questions about employment were also asked, which were intended to give the government an idea of which industries were in decline, and which were growing. Interestingly, many respondents provided much more information than was needed with people giving the name and sometimes address of their employer in addition to the industry that employed them. These questions were later incorporated in the 1921 census. There are three other points of interest in the 1911 census. Firstly, the enumerators tried to approximate the homeless population, albeit with little success. Secondly, some women’s details are missing. This was due to the campaign for women’s suffrage, as many suffragettes protested by refusing to be counted in the census. Finally, for the first time, the original census forms (in the handwriting of the householders) were preserved, and it is these that you see when looking at the census online.

Cheltenham Workhouse 1891 census return page 1

From the 1851 census onwards, special enumeration books were used for institutions such as workhouses, army barracks and hospitals. The results are included in the usual returns, so you need to know where the institution was located in order to check the right enumeration district. Workhouse census can be desperately sad things to browse. A quick glance reveals mostly elderly people who can no longer work of those suffering from physical or mental illness. In this example the oldest person is Edward Averiss, an ‘ag-lab’ aged 79 (on line 2), while the youngest is Henry Birt, aged 11, and described as an ‘Idiot from childhood’ (on line 24). Looking at those with mental illness, seven people here as listed in that category, almost a third of the total. Married couples can also be seen as well, such as John & Rhoda Bayliss, aged 71 and 69 (on lines 19 & 20). Families were often taken in as a group and an example here is the family of the already mentioned Henry Birt, who was in the workhouse with his mother Ann and his siblings Charles and Mary-Ann.

Gloucester gaol

Census returns were compiled for prisons – this is a page from the 1881 census for Gloucester prison. Oddly, they did not always get a special enumeration book but were simply included in the relevant enumeration district. Prison census returns are fascinating primarily because they hold such a wide range of (usually) the lower classes in terms of employment and abode. They do not contain details of why inmates were imprisoned so if you wanted to find out why a person was in prison, you need to consult the relevant gaol registers.

1871 Census return for canal boat Garibaldi

Special enumeration forms for vessels were introduced in 1851, but none are known to survive so in practice 1861 was the first census to include returns from shipping – both the Royal Navy and merchant shipping, at sea and in ports at home and abroad. The Master of the vessel was responsible for completing the forms and the instructions indicated that the completed form should be handed in to HM Customs with the ‘least possible delay‘, or face a fine of £5. Despite this, the nautical returns are far from complete due to the difficulties of collecting enumeration forms from ships at sea or in distant ports, etc. Shipping included local barges working only inland waters – this is part of the 1871 census return for the canal barge Garibaldi of Lechlade, which worked the Thames & Severn Canal mostly carrying coal, salt and corn.

1881 Census return for canal boat 'Frederick Williams'

Census returns for boats and ships followed the same format as those on land. This return for the canal barge Frederick Williams, a canal boat based at Brimscombe port on the Thames & Severn Canal shows that her Master was William Rice and onboard with him was his wife, Eliza and their young sons, Thomas and Joseph, together with Thomas Blinkworth, a waterman who was the deckhand.

1881 Census return for the Severn trow Wherry

Ships can be found well away from where they should be and so sometimes an idea of their usual voyages or movements can help. This image shows the 1881 census for Arlingham District 2 and has an entry for the ‘Wherry’, a half-decked Severn trow with a crew of three - William Bodman (50), Henry Haywood (43) and John Willivoize (25). On census night, this vessel was probably anchored on the riverbank at Arlingham, waiting for the tide in order for her to proceed downriver. However, it is interesting to note that John lived at Arlingham, and his family is shown directly above the entry for the trow, so you can’t help but wonder whether they moored to the bank by his house in order to get some home-cooked food!

Rank, profession or occupation

This column is probably one of the best aspects of the census. There are around 1,333,792 occupations given in the 1881 census and they range from an Abecedarian (an alphabet teacher) to a Zythepsarist (a type of brewer). This example, from the 1881 Arlingham census has scholars, a stay maker, laundress, carpenter, carpenter’s wife, grocer, grocer’s assistant, waterman, a pair of ‘former’ labourers, and a retired lady.

Occupations in Cheltenham workhouse 1901 census

This extract is from the 1901 census for Cheltenham workhouse and shows how the census can be used for social history. As well as the ‘usual’ jobs - such as laundress, general labourer, charwoman, etc, there’s a fly-driver, a sawyer, a brickmaker, Gentleman’s servant and a ‘Scavenger for the corporation’. However, most telling here is that many of these souls in the workhouse have the abbreviation ‘Ret’ – meaning retired – attached to them; a harsh reminder that most elderly folks ended up in the workhouse when they’re working days were over.

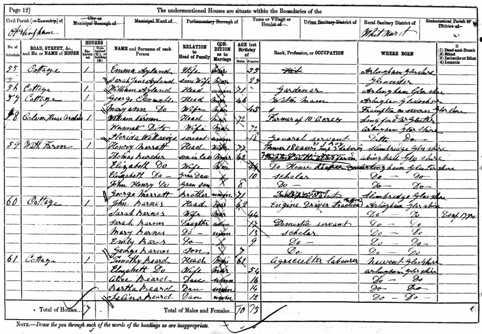

Farms in the census returns

In rural locations, the size of farms was usually given in the ‘rank, profession or occupation’ column of the farmer, as this example from Arlingham the 1881 census – where farms of 10 and 18 acres are listed. These also usually gave the number of men that the farm employed in the case of the 18-acre Warth Farm run by Henry Merrett shown here, the workforce comprised a boy and 3 labourers (one of whom was the farmer’s son-in-law). Also of interest in this census is John Barnes, whose occupation was given as ‘Engine driver traction’.

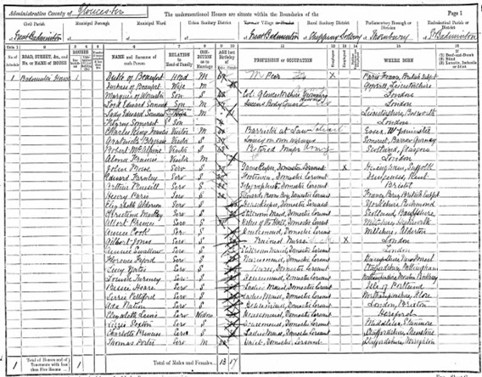

1891 Census – Clanna Falls House, near Lydney

Upper class households are always interesting, mostly for the staff that they employed. Here at Clanna Falls in Lydney (a modest country house in what was considered somewhat of a rural backwater compared to the rest of the country), the staff consisted of a butler, footman, cook/housekeeper, ladies’ maid, 3 housemaids, kitchen maid, scullery maid, nurse, governess, coachman and 3 grooms. Of interest is that an adjacent property was utilised as servant’s quarters as it contained the coachman, Thomas Joseph and his family, and the three grooms.

1891 Census - Badminton House

Some upper-class households were larger than others! This is first page of the 1891 census for Badminton House. It runs to 4 pages worth of census returns – amounting to 65 staff & servants. At the time this was for just six family members and four visitors. It is not known who compiled the returns for the house. Although technically it should have been the Duke of Beaufort, one suspects that it fell to the House Steward, who is listed on page 2 of the return.

1901 Census – Pittville Circus, Cheltenham

Upper class ‘town houses’ tended to operate with fewer staff – this is from the All-Saints area of Cheltenham centred on Pittville Circus. It was realm of retired army officers, lawyers and others ‘living on own means’. Most of these houses were run with just the help of a few domestics, typically including a cook, a housemaid and a few others.

1901 Census description of enumeration district for Abenhall

Upper class ‘town houses’ tended to operate with fewer staff – this is from the All-Saints area of Cheltenham centred on Pittville Circus. It was realm of retired army officers, lawyers and others ‘living on own means’. Most of these houses were run with just the help of a few domestics, typically including a cook, a housemaid and a few others.

1901 Census for Allen J Barnard

This entry shows Allen J. Barnard in the 1901 census, living at the Judges Lodgings just above Abenhall on Plump Hill. Interestingly, this shows his father as James Barnard but Allen’s baptism which took place at Abenhall Church in 1874, shows his parents as Willan and Mary-Ann Barnard.

1911 Census for Allen J Barnard

By the time of the 1911 census, Allen was making a living as a cattle farmer at Plump Hill, not far away from his birthplace at Abenhall. He had married a Cinderford girl, Alice, and they had 3 daughters. Who knows where he will be in the 1921 census? We’ll find out soon.