Introduction

For most of our history England has been a patriarchal society, and women have had more limited life-choices, less access to employment and trade, and fewer legal rights than men. It was only in their homes and communities that women could exercise informal power, frequently taking on strong roles in culture and spirituality. The advent of Reformism during the mid-1800s finally allowed issues facing women to start to be addressed. The First World War advanced the feminist cause for it triggered social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reform that culminated on 14 December 1918, when women voted for the first time in a general election. Women appear more often than is probably realised in the archives, but considering their role in society over time, probably not enough. This exhibition takes a look at women in the archives, an eclectic mix of all types of documents to show how much society owes to the fairer sex.

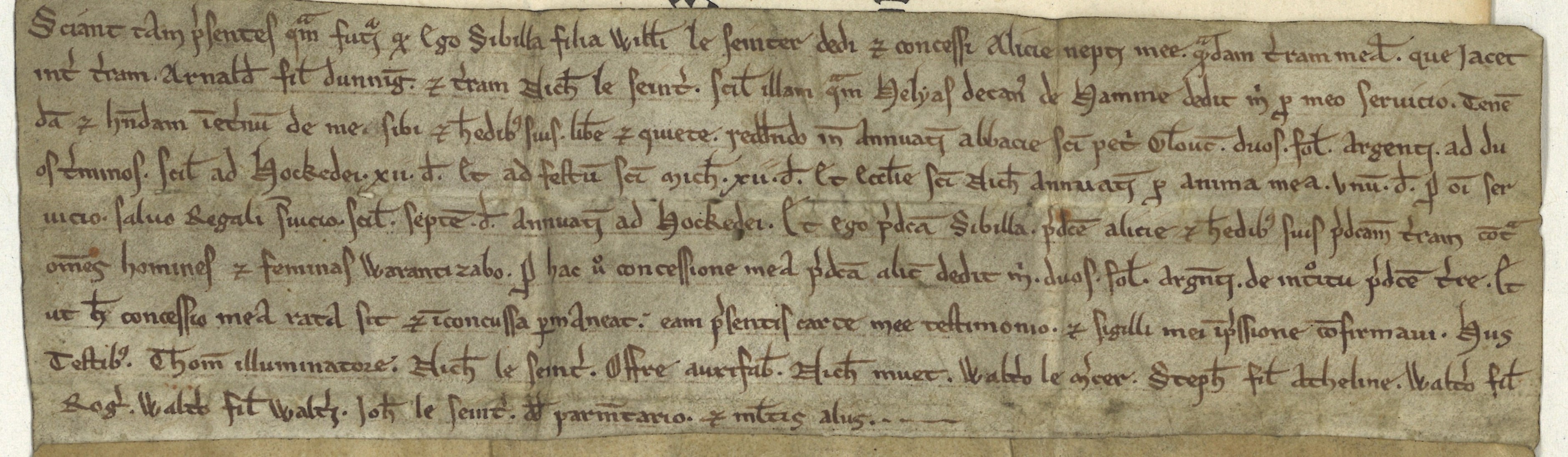

Grant from Sibilla, around 1190

The oldest document in the Archives with a distinct named woman – i.e. not a wife – is dated c.1190 and is for a grant of land from Sibilla, daughter of William the Girdler (beltmaker), to her niece, Alice (which makes her the second named woman!). The land had been given to Sibilla by Helias the Dean of St. Peter’s Abbey for her service. In typical medieval fashion, it doesn't say where the land was except that it lay between the land of Arnald and Nicholas the Girdler (who was also a witness), but we presume it was in the city. There were several witnesses – all male: Thos the Limner (painter) Nicholas the Girdler, Offre the Goldsmith, Nicholas Muet, Walter the Mercer, Stephen son of Atheline, Walter son of Roger, Walter son of Walter, John the Girdler and David the Parmenter (tailor).

Red book of Gloucester

In 1504, Gloucester believed it had a shameful reputation for immoral living and the Borough decided to clean up – before God did it first! This extract from the Borough Council’s Court Leat minutes ordered that ‘notorious qwenys’ (prostitutes) were to be given 'frontlets of paper and hoods’ and then – as noted in the margin as ‘Whores to be carted‘ – they were to be shamed by being put in a cart and paraded around the town. Typically, most of this item is male orientated and sets out the fee paid to the ‘halyer’ for each time he takes his cart round, the fine levied if he doesn’t do this when required and the fine levied on the Sheriff and his officers if they didn’t attend! The minutes go on to say that ‘wedded men and priests and other common qwenys whether she be mannys wyf or single woman’ who consorted with ‘horres, strompetts or with meanes wyffes' were to be brought to the ‘Which’ – we think this is ‘cwtch’, the Welsh word for a cupboard or cubbyhole (or a cuddle!) – which was a cage in the marketplace, used to imprison offenders. Repeat offenders were either banished or threatened with the pillory if they did not comply - the stocks and pillory stood in Southgate Street, adjacent to Love Lane (the importance of which might be obvious!), making punishments extremely public.

Magistrate's court minutes (Cheltenham Petty Sessions Division) 22 July 1834

As might be expected in a patriarchal society, it was always the women who got into trouble with the law over prostitution – never their male clients. This is from the Cheltenham Petty Sessions for 22 July 1834 and records the charging and sentencing of two prostitutes, Jane Cook and Emma Yandal for behaving in a ‘very riotous and disorderly manner’ at 11.30pm. The minutes state that the women were reported by one Robert Green. The entry does not suggest that this man was an officer of the law and so it seems that he was a member of the public. Given the time that he witnessed the women, one wonders what he may have been doing out and about at such a late hour. Was he a potential client that the girls refused? Cook was given two months and Yandal one month imprisonment in Northleach Gaol, both being classed as ‘rogues & vagabonds’.

Ann Beach's domestic account book , March 1747/8

Keeping the household was the one area where women dominated, and they could (and did) exert a lot of control and power when it came to running the house. In most instances, men just signed the cheques or handed over the cash! Taken from the archive of the Hicks-Beach family, this set of accounts from the domestic account book of Ann Beach the younger of Netheravon includes money paid for household goods (sugar, oatmeal, beef, veal, calves head, milk, mutton, butter, etc) as well as snuff, tobacco, ‘bisketts’, a tip to a maid and a washer woman. It also records the lady of the house having to pay her gambling debts – including paying out money to her husband on several occasions!

Ann Beach's domestic account book, October 1749

One of the most difficult and dangerous times for a woman in the past was childbirth. Postpartum confinement was (and still is) a traditional practice following childbirth. The seclusion or special treatment lasts for a culturally variable length: typically for one month or up to 100 days. The practice used to be known as ‘lying-in’ and is a recuperative period that centres on bed rest and various care practices. This page – another from Ann Beach's domestic account books – includes references to expenditure on the birth of her daughter Ann, also known as "the Child” in October 1749.

30th paid Mary atwood for being here Ten days when I lay in……. 6s 8d

paid mary atwood and her girl for sitting up 4 nights at 1s per night……. 4s

paid old nurse for five weeks…… £2 8s 0d

paid nurse Sturges for six weeks at 5s per week…... £1 10s 0d

Lower class women also ‘laid in’ but with less hygiene and generally more squalid conditions, it was far riskier. Postpartum infections – also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever – were common and often deadly.

Arlington Row, Bibury, around 1890

Before the Industrial Revolution, most of the workers in the textile industry were women with hand spinning being having a 100% female employment. Spinning and weaving was carried out under the ‘putting-out’ system, whereby workers would take raw materials from a merchant, spin or weave the materials in their homes, and then return the finished product and receive a piece-rate wage. This is Arlington Row at Bibury c.1890 when the cottages and their attics were let to tenant weavers – some of whom are no doubt seen here. Weavers would utilise water flowing along the mill leat to wash fleeces and the cloth they produced which would then be hung to dry on racks on ‘Rack Isle’ on the left.

Chalford Post Office staff, around 1900

This is the Postmistress and staff – two female clerks, 6 postmen and a postboy – of Chalford Post Office in 1900. Women were only officially employed by the Post Office after 1870, but prior to this they could work as Sub-Postmistresses, undertaking postal duties on a commission basis in addition to their running their own businesses. An example is Flora Thompson’s Dorcas Lane in Lark Rise to Candleford, who was a sub-postmistress but also the owner of the adjoining blacksmiths, which she had inherited from her father when he died. The postmistress here was unmarried – if she married, she would have had to resign her post – still at least she didn’t have to deal with the Horizon IT system!

Mr & Mrs Sims of Brockworth, undated

This is Mr & Mrs Sims of Brockworth and I’m sure you’ll agree that the good lady here does look rather formidable! Sadly, we know very little about them – but I think we can be pretty sure ‘who wore the trousers in the house’ as the old saying goes. You also can’t help but wonder whether Mrs Sim’s rather imposing look was required to handle the apparent cheekiness of her husband! This couple could almost have come straight out of ‘My Uncle Silas’ by H E Bates!

Ladies from the Bazley and Webb families of Hatherop, c1899-1900

It is a fact that much of our photographic archive relating to women comes from the upper and middle classes – simply because they had the time and equipment to record their lives in a way that the lower classes couldn't, as emphasised by this rather stylish picture. It comes from a photograph album of the Bazley and Webb families of Hatherop and shows a pair of elegantly dressed ladies sitting on a garden seat on a sunny day. Sadly, we don’t know where they are, as the album is a classic family album with a mix of views of members of the family in Hatherop, Scotland, France and Algiers, between the years 1899 to 1900. They do, however, appear to be ladies of leisure.

Aunt Prowse's diary, 1765

Many upper-class women recorded their lives in diaries. This diary page comes from the Sharp family papers – an archive that spans the late 17th to mid-19th centuries and covers four generations. The family was not particularly wealthy, so sons had to make their own way, while the daughters were married off. Among them was Elizabeth Prowse, nee Sharp, of Wicken Park, Northamptonshire, who kept a diary that was later copied as "Aunt Prowse's diary“. This 1765 entry made by Elizabeth is typical – a listing of visits, teas, dinners and supping…

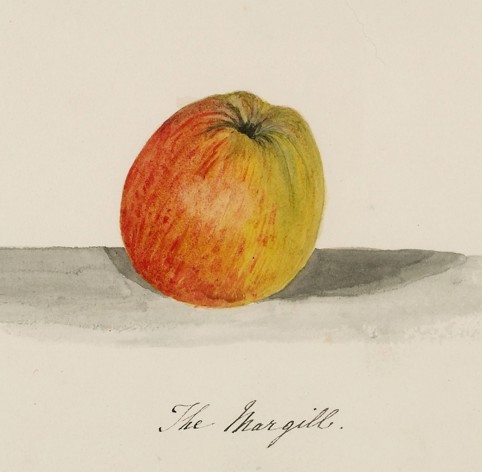

Margill apple by Mary Baker, around 1800

Another member of the famous Sharp family was Mary Baker, nee Sharp (1778-1812). In May 1800, she married Gloucestershire man Thomas J Lloyd Baker and the couple lived at the family seat, Stouts Hill at Uley – which in 1935 became a prep school and later boasted Stephen Fry and Rik Mayall among its pupils! The couple had one son, but Mary died prematurely in 1812 at the age of 34. However, prior to her death, she had written poetry and become a skilled artist. Mary was very interested in fruit trees and produced a series of exquisite watercolours of various types of local apples – some of which are seen here and were used in correspondence concerning specimens, varieties and tips on cultivation with other growers.

Gloucestershire Archives reference D3549/24/1/1

Original Drawings of Botanical Specimens by Anne Hill

In July 1941, Anne Geraldine Hill of Southend House, Tewkesbury gave a series of sketch books to Cheltenham Public Library. They had belonged to an ancestor, Miss Anne Hill of Rudhall, near Ross. Little is known of Anne the painter, who died around 1862 and was buried at Bromesberrow, near Ledbury – but her sketch books, entitled ‘Original Drawings of Botanical Specimens’ contain some exceptional watercolour drawings and paintings.

Farmer’s wife, Charringworth Chase Farm, Charringworth, c1910

This photograph of a farmer’s wife in her spotless apron feeding turkeys was taken in the farmyard of Charringworth Chase Farm, Charringworth in the early 20th century. While male farmers tended to do field and forest work, look after the large animals and undertake farm maintenance, women did most of the rest! They brewed beer, handled the milk and butter, made cheese, raised small livestock (notably pigs) and poultry, grew vegetables and fruit, spun flax and wool into thread, sewed and patched clothing, and nursed the sick. However, they would also do field work at harvest and haymaking, and in war time, many turned their hands to heavier work such as ploughing.

Gloucestershire Archives reference D11554/1487

Butter making, Rodborough, 1909

This photograph was taken at Sir Alfred Apperley’s Model Dairy Farm at Rodborough in 1909 and shows the final stages of butter making. The milk has been churned in a vertical churner – this was a task often undertaken by men as all it required was strength to rotate the butter churn. After churning, the churn was emptied and then it was the task of the girls here to undertake the more skilled task of using a pair of wooden butter pats to blend salt through the butter and then to press it into blocks to remove the watery buttermilk. It would then have been wrapped in waxed paper and stored or sold.

Ann Wheeler, midwife, Moreton-in-Marsh, 1922

This is Ann Wheeler, a midwife of Moreton-in-Marsh taken upon her retirement in 1922, aged 76. She was described as an ‘old school maternity nurse’, implying that she hadn't been formally trained. Midwifery was only legally recognised in 1902 with the Midwives Act, when to be a midwife a woman (men were barred from midwifery between 1902 and 1979) had to be trained and examined by the Central Midwives Board. However, before World War 1, as there were so few trained midwives, most rural and working-class women were attended not by a professional midwife but by a local woman, albeit one with lots of experience. In her 46 years of service, Ann had attended over 1,000 births.

Surgeon's bill for bleeding, 1826

Those who received poor relief were also cared for medically if they fell ill. This page from the Upton St. Leonards overseers’ records for 1826 details visits made by the surgeon George Rodway to the parish of Upton St Leonards for bleeding various women. At this time ‘bleeding’ was thought of as a tonic or ‘pick-me-up’ that was considered beneficial to health. This bill for bleeding and travel expenses for 14 women came to 12s 6d (£42 today).

Removal order for Elizabeth Boucher and son, May 1848

Women tended to be the subject of more parish settlement examinations and removal orders than men – as it was the men that normally left them. This is typical – the removal order of Elizabeth Boucher and her son (Charles, aged 1) from the parish of Kings Stanley to the parish of Cam in 1848. The family had moved to Kings Stanley but Elizabeth’s husband had then deserted her and, without any means of support, she had been forced to turn to the parish overseers for help. After a settlement examination, they applied for the removal order to send her from Kings Stanley to Cam, which became her place of legal settlement. By this date, this meant Elizabeth and her son went straight into Dursley Workhouse.

Transportation bond for female convict , 6 April 1756

This is part of a transportation bond authorising Mr Heming and Mr Heath to transport Mary Frances and three male convicts on 6 April 1756. Mary was convicted of Grand Larceny (the theft of property valued at over 12d) – after confessing to the theft from the house of Jane Oakley of a mop hat, a cap and pinny and an Indian handkerchief. She was sentenced to transportation to the American colonies for seven years. She would have been taken with the other convicts to either the prison hulks at Woolwich or Portsmouth to await transportation. However, unlike their male counterparts, women convicts were not placed on the hulks. Instead they were held in local prisons – often Millbank Prison (if bound for Woolwich) or Portsmouth Borough Gaol.

Photograph of women munitions workers at Quedgeley, 1917

The First World War brought many changes in the lives of women and although it is often presented as having had a wholly positive impact, opening new opportunities in the world of work and strengthening their case for the right to vote, not all the war opportunities were positive or long lasting. The Canary Girls were women who worked in munitions manufacturing trinitrotoluene (TNT) shells during the First World War (1914–1918). The nickname arose because exposure to TNT is toxic and can turn the skin an orange-yellow colour reminiscent of the plumage of a canary. Locally, women worked in National Filling Factory No.5 at Quedgeley, a 308-acre site that began production in March 1917, which at its peak, employed around 6,300 local people of which over 5,000 were women. This photograph shows some of the women munition workers from Quedgeley on a day-trip to The Red Lion at Wainlodes in 1917. Sadly we don’t know why these particular women were on the trip.

Lady archers, Forthampton House, c1870

Until the late 1800s, opportunities for women to take part in sports were limited. The main sports were those that required little physical exertion such as croquet, bowls or – as seen here – archery. Taken at Forthampton House, this shows Mrs J R Yorke, Madam de Brienen and Mrs Langhorne at archery practice at Forthampton Court gardens, around 1870. Archery was a popular female sport because women could wear the fashions of the day and it even became an acceptable area to display marriageability! A guide to country pursuits coyly remarked that “few exercises display an elegant form to more advantage”.

Inventory of Joan Paynter, 1696

From 1530 to 1782, every executor of a will had to appoint three or four local men to appraise or value the deceased’s personal estate and provide the probate court with a full inventory or list of goods and their value. Anglo-Saxon laws allowed women to own their own property before and after marriage, but after the Norman Conquest, English common law (a hybrid of Anglo-Saxon and Norman traditions) led to the creation of coverture, where married men and women were considered as one financial entity. This meant that married women couldn’t own property, run businesses or sue in court. However, unmarried women and widows did enjoy those rights. Joan Paynter,as well as being a property owner (109-11 Westgate Street in Gloucester) was also a businesswoman, as one of these properties was a brewhouse which was rented out to a brewer. Her probate inventory gives a good idea of how many possessions she had, as its valuation came to £109 2s 3d – approximately £22,428.60, which did not include the value of her land and property. The law was eventually changed with the Married Women's Property Act 1882.

Inquest of Harriet Hawkins, 26 January 1865

Men feature more in coroner’s records because they were involved in more dangerous outdoor activities. Women experienced more domestic related deaths – falls and burns – but many deaths were recorded as ‘Visitation of God’ – which covered many medical causes. Intemperance was also common – this is the inquest for Harriet Hawkins, 35, an inmate of Clifton Union Workhouse. She died on 26 January 1865 of a Visitation of God because of being ‘Drunk since Christmas’

Pancake Race, 1973

Rather like a Mums’ Sports Day race at school, it’ll be all smiles at the start, but you just know that this Women's Institute pancake day race will be a bloodbath with elbows in faces, trips and shoving! The ladies near or on the verge won’t stand a chance, and within 10 seconds will be in, or more probably over, the hedge!